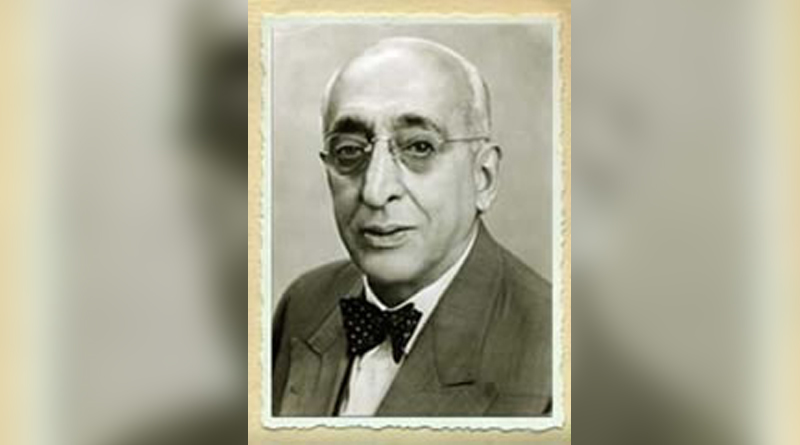

On the ideological inclinations of Indian business houses in the colonial era, Political Scientist Stanley Kochanek makes an interesting generalisation. The Bombay-based business houses sought to cooperate with the British Raj while the Marwaris were mostly aligned with the Gandhian, nationalist Congress. The businessman cum politician Homi Mody fell in the former faction. Temperamentally liberal and a constitutionalist, Homi Mody straddled the public life in both colonial and Independent India as a member of two outsized minority groupings, i.e. big business and Parsis. Mody’s relative obscurity in all the flavours of the “idea of India” warrants a novel approach towards engaging with India’s past.

A brief career sketch of Homi Mody would help make the point clear. In the political domain, he was the member of Indian Legislative Assembly (1929-43), Viceroy’s Executive Council (1941-43), the Constituent Assembly (1948-49); a participant in the First Roundtable Conference (1930) to represent the Indian commerce and industrial interests; a delegate to the ILO Conference (1937) in Geneva; an appointed governor of Bombay (1947); and the Governor of UP (1949-52). In the business domain, he was the president of the Bombay Mill Owners’ Association, the Indian Merchants Chamber, and the Employers’ Fund of India; the chairman of the Associated Cement Companies and the Central Bank of India; a founder of the Indian Banks’ Association; and a close aide to the House of Tatas.

Homi Mody’s politics during the colonial period was limited to the domain of the legislature and civic activism. He wasn’t associated with any political party and mainly served the interest of the Bombay business. The British policy of functional representation in the assembly ensured his membership in the legislative body. In this regard, he stood out from the Congress nationalists, Communists, the Muslim League, and Hindu Mahasabha politicians who indulged in the politics of masses. In fact, Mody often came at the receiving end of the brickbats of Congress politicians and the nationalist press for his close association with the Raj.

As the Indian nationalist triumph in 1947 has come to guide history-writing, political figures like Mody remain marginalised because their roles don’t fit in the grand narrative of the Congress nationalist struggle. However, the colonial period saw varied “Indian” actors, strategies, and interests at play that didn’t necessarily conform to Congress nationalism but deserve due recognition. Mody’s politics as such could be categorised as liberal, albeit with certain caveats.

Mody’s biographer called him a liberal by instinct in the mould of Pherozeshah Mehta. Mehta was also his political mentor, argues his biographer. Interestingly, both Mehta and Mody were Parsis who came to dominate the Bombay municipality. During his long stint with the Bombay municipality, Mody led the Progressive group against the Congress nationalists. His focus mostly lay on addressing the administrative issues plaguing the city. In the early 1920s, he was an active advocate of Home Rule. In 1928, he protested against the appointment of an all-white Simon Commission. Later in 1943, he would resign from the Executive Council as a protest against the Viceroy’s failure to release an ill Gandhi on fast. But, his belief in constitutionalism made him averse to the Gandhian methods and philosophy. In this sense, he was close to the liberals like Sapru and Sastri. But, he wouldn’t join the National Liberal Federation because they were too “spineless” and vacillating for him.

In contrast, Homi Mody’s interests compelled him to advocate for the business community with a decisive fervour, largely on account of his oratorical skills. His pithy speeches laced with witty quips would receive special mention in the press. Not to mention, they also landed him in unsavoury controversies.

It is in his advocacy of Indian industrial interests that Mody takes an illiberal turn. His constant prodding for tariff protection, calls for serving’ national interest’, criticism of ‘consumers’ interest’ arguments, cartelisation of the textile market based on the Bombay-Lancashire collusion in the Mody-Lees Pact, etc. perfectly fits in the framework of pro-business policy. In fact, on his retirement from the chairmanship of the Bombay Mill Owners’ Association, the Indian Textile Journal called him “an ardent protectionist” in its glowing tribute! In the wake of heated assembly debates, Mody would champion economic nationalism to counter the free-market policy. For instance, at the annual meeting of the FICCI in February 1930, he moved a resolution favouring the Coastal Reservation Bill and hit out at the opponents:

“Somehow or other, whenever national industries of the country were going to be protected, this bogey of consumer’s interests was trotted out as if these people whose Business it was to throttle the economic progress of the country were all the time doing so because they felt for the dumb millions of the country and poor inarticulate and unfortunate consumers.”

Today, Homi Mody’s attitude may come as a surprise to Indian liberals who see him as one of the founding members of the Swatantra Party, featured on the Libertarianism blog. But, the colonial-era liberals were the champions of economic nationalism. Gokhale argued for the infant industry protection; Dadabhai Naoroji propounded the drain of wealth theory; Justice Ranade criticised the conservative statesmen for sacrificing Indian interests in the name of free trade. Like the earlier group of liberals known as the Congress moderates, Mody sought to tread a fine line between the full-blown nationalism and cooperation with the Raj. Mody held the demand for dominion status desirable; supported the Hindu Child Marriage Bill; and approved of the federal scheme during the first Roundtable Conference. He was also an enthusiastic supporter of the 1918 Montagu-Chelmsford reforms and the 1935 Government of India Act. In these regards, he was no different from his liberal predecessors.

The making of the Indian Republic brought with it uncertainty as the state-business relation was open for negotiation and reshaping. The provision for the universal franchise came along with an end to the functional representation. In terms of economic policy, the state-led centralised planning was seemingly poised to play a significant role, as evident from the constitution of the National Planning Committee in 1938. The capitalist tycoons made a pact with planning-driven development. They came with their own version – the Bombay Plan of 1944. Mody was no exception. He “whole-heartedly welcomed the appointment of an Advisory Planning Board” by the interim government in 1946. Soon followed the December 1947 Tripartite Industrial Conference, with the state, industrialists, and labour being the parties. The outcome was the Industrial Policy Resolution of 1948. The resolution, writes Shankkar Aiyar, “paid obeisance to Gandhian thought, was socialist in tone and business-friendly in content.” The respite, however, was short-lived.

In February 1953, Homi Mody attacked the government policy towards the private sector for the first time. In his speech to the Employers’ Fund of India, he criticised “the flow of labour legislation, irksome control over profits, production and distribution.” In January 1956, he was part of the delegation of industrialists to the PM Nehru. In an off-the-record meeting, he pointed to the deviations already made from the 1948 IPR and drew attention to the difficulty of doing business in the license-permit Raj.

The arrival of the Second Five-Year Plan in 1956 entailed full-blown state domination of the economy as the Mahalanobis model sought to develop India in its image. Homi Mody criticised the Plan for being too ambitious in the wake of constrained resources. Mody’s discontent was shared by a bunch of public-spirited professionals and leaders. BR Shenoy was the part of the advisory committee of the economists to the Second Five Year Plan and had written a note of dissent to the proposed measures. Rajaji’s columns in the Swarajya were increasingly turning critical of the centralisation in both economy and polity. Minoo Masani was battling the communist propaganda in the public sphere with his Democratic Research Service, Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom, and Freedom First magazine. It probably was their close association with the Tatas that brought Mody in contact with Masani.

The incorrigible Masani persuaded Homi Mody and a few other friends to fight the 1957 general election. The idea was to form a grouping of independent parliamentarians to challenge Congress domination. Mody lost to the local Congress candidate and only Masani managed to reach the Lower House. The defeat, however, didn’t dampen Mody’s attacks on government policies. For Homi Mody, excessive regulation and increased outlays on planning posed a threat to economic freedom inherent in a democracy. He would use the business organisations’ platform to voice his criticism.

The political consolidation of disparate oppositional voices was enabled by the 1959 Congress Resolution at Nagpur proposing cooperative farming. The resolution came out in January, and in the next month, Homi Mody stressed the need for a new party. The enterprising Masani was on the task and managed to persuade Rajaji to come on the board. He had also approached JP though the venerable Gandhian declined on the ground of his retirement from party politics. With Rajaji in charge, the formation of the Party was announced publicly in a 4th July 1959 meeting. Masani wrote to Mody on 19th June offering a position in the organising committee. Mody accepted the offer and came on board as the treasurer.

Pundit Nehru and other detractors of the Party called it a party of frustrated old people championing the reactionary and business interests. A 1967 analysis of political donations, however, shows that the Congress received almost thrice as much from the business houses than the Swatantra. Political scientist Howard Erdman has also pointed out the difficulty for the Swatantra party in attracting donations from the business houses. No less than Rajaji bemoaned the unfair charge: “Calumny has had a start, and it keeps on maintaining the falsehood that the Swatantra Party is a rich men’s lobby. The rich men know where to go; they go to the Party in power.”

As a member of the “inner circle” of the Party, Homi Mody mostly addressed the public meetings criticising the economic and foreign policy of the government. For instance, in an article published in 1965 by the Forum of Free Enterprise, he criticised the continued infatuation with planning despite repeated failures:

“Agricultural and industrial production is stagnant—there have even been signs of a recession—and there are shortages in practically every commodity and service. But that does not seem to dampen the enthusiasm of the Planners who, as soon as a plan is nearing its end, are ready with another.”

Homi Mody enunciated the Swatantra principles in terms of democratic freedom, social justice, and efficient administration. In the domain of foreign policy, Mody and the Party both advocated a pro-western stance and were critical of the NAM posturing. In the wake of China’s India war in 1962, Homi Mody criticised Nehru’s conduct, “Our so-called neutrality has brought us very few friends, and it is time the Prime Minister stopped airing his concepts of international diplomacy which have landed us in so many difficulties.” In one of his public speeches, he also criticised the Defence Minister VK Menon’s decision of continuing the support to China for its UNSC membership. He demanded the withdrawal of the Indian ambassador to China; resignation of the Defence Minister; and constitution of a National Defence Council to enable effective decision-making for the war.

For all his eloquent witticism, Homi Mody’s role in the Party seemingly was limited as he catered to the westernised, English-speaking, urban constituency of business interests. Nonetheless, it is no unremarkable feat for him to go against the grain when opening up against the government could do real damage to his personal business interests. It becomes more evident when putting in the context of his earlier moderate conduct in the Raj years, maintaining a delicate balance between the colonial administration and the Congress nationalists. What, however, explains the transition of the temperamentally liberal Mody from being a pro-business to a pro-market politician? Mody’s biographer suggests an answer. The political philosophy, in Homi Mody’s case, was guided by a sense of practicality that sought to gain concession without consternation. As the broader context of the political economy changed, Mody’s response invariably varied. What remained constant, though, was his liberal conviction and sense of humour.

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.