Early in my schooldays I was taught that 14 November is ‘Children’s Day’ – the birthday of India’s first and the longest serving Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who was known for his passion for the welfare, education and development of children and young people.

There used to be biographical sketches in textbooks and essay writing in exams on the life of Nehru, especially on his connection with children. Maybe he loved children, and maybe he had their best interest at heart but his policies practiced over an extended period of time (remember, he was the Prime Minister for 17 years) bore little fruit, and more importantly, caused immense misery, as evidenced in the anemic rate of rise in standard of living of India’s masses.

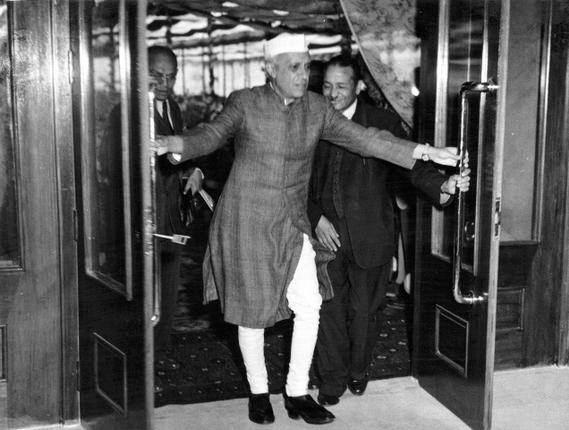

Figure: Jawaharlal Nehru – Opening Doors to Nowhere

Image Courtesy: The Hindu

Many are quick to discount Nehru’s mistakes. It is as if, even otherwise smart and articulate people find it hard to bring themselves to point fingers at our beloved Chacha, the title thrust upon us by our public schools. They cite several reasons for it.

Apologists say – But he was the first Prime Minister, he had no blue print. We have the benefit of hindsight.

To them I say – True. But he did have instances of various countries experimenting with varied models at the time. Many European countries in post-World War II period went for greater role of government in economic affairs and fared poorly. These could easily have been contrasted with the examples of West Germany and Japan which witnessed fast growth. Maybe Nehru was an ostrich who had buried his face in the sand. All he needed was to see what was happening in the world around him – what experiments were successful and what weren’t – and choose the one that was producing results. Instead, he was dogmatic in his approach and continued repeating his mistakes in the hope that somehow the same policies would start producing different (better) results.

Apologists say – Nehru’s policies of centralised economic planning were necessary for the state of development India was in. It required state mobilisation of the few resources that India had at the time so as to channel them into areas which required immediate attention (investment).

To them I say – Yes, India had few resources at the time. But their efficient use did not require their allocation and management by the government. Economist Milton Friedman writes in his Memorandum to the Government of India in 1955, “It is impossible to predict in advance the lines of investment that will turn out to be the most productive, as the failure of so many private enterprises amply demonstrate. There is therefore great need for a system that is flexible and can change easily.” Similar thoughts and sentiments were also presented to and impressed upon the Government by economists B R Shenoy and Lord Peter Bauer, industrialist A D Shroff, and many others. Sadly, all these voices were summarily ignored.

Apologists say – But Nehru contributed immensely to the establishment and strengthening of India’s democracy. So what if he messed up a little with the economy.

To them I say – You are sadly mistaken. The planners failed to realise that the kind of planning they were hoping to put in place required employing of totalitarian devices, which in turn severely undermines their own God – Democracy. Granting special favours to particular firms in the forms of advantageous loans, guaranteed markets, refusal of licenses to competitors, enforcing or permitting private price-fixing, deficit financing, are but a few measures through which the government restricted individual freedom and weakened democratic institutions.

“I believe, as a practical proposition, that it is better to have a second rate thing made in our country, than a first rate thing that one has to import.” – Jawaharlal Nehru (From a speech in the 1950s)

Yes, Nehru wanted efficient use of resources!

Nehru’s stated hatred and distrust for capitalism and profits caused businessmen and market’s profit-loss mechanism to be replaced by bureaucrat run public sector enterprises, which were a huge misallocation of scarce resources, whose efficient allocation Nehru set out to achieve.

Today when many celebrate Nehru’s 125th birthday with deep reverence, I can’t keep myself from blaming him for decades of poverty that my grandfather and father had to live through. I don’t have mixed feelings about it either.

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.