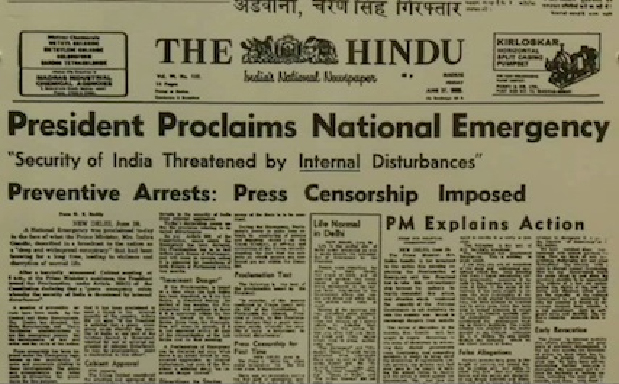

The following piece contains excerpts from a monograph published by Forum of Free Enterprise titled ‘Press Freedoms and Human Rights (1977)’. The author is C R Irani (1931-2005) who was a prominent Indian journalist and the Editor-in-Chief of The Statesman. Mr Irani was widely admired for his criticism and staunch opposition against Indira Gandhi’s policy of press censorship during the state of emergency proclaimed in 1975.

“You did not even attempt to rattle your chains, let alone try to break them.”

Freedom of speech and of the Press is specifically embodied in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The concept is in two parts – one, the right or freedom to form and hold opinions without interference, and its corollary, the right to dissent without fear of consequence; and, two, the right to a free and uninterrupted flow of information, to seek, receive and impart information without let or hindrance because only then can a fully informed opinion be formed by the citizen and by citizens in their collective society.

Now, I come to a basic question of our times. It was Solzhenitsyn, the well-known Soviet dissenter, who posed this question as to why it was that free people everywhere – in his language, those who “soar unhampered over the peaks of freedom” – lose the taste of freedom, lose the will to defend it, and hopelessly confused and lost almost and began to crave slavery. This is a large question and men of good will everywhere must give a lot of thought to it. One conclusion can safely be drawn from the available evidence – free people find themselves in this situation because they are not prepared to pay a continuing price for their liberty. It is only this unwillingness to pay a proper price for liberty that seduces people to slavery.

In the context of what happened to the Press in India, the first point to notice is that the Press was not suddenly inflicted with controls and restrictions in the middle of 1975. To be fair, the story goes back much farther. The attack on the Indian Press started in the middle of 1969 when the then Government decided that a free Press was inconvenient.

The carrot-and-stick policy was adopted at about that time. The carrots are very obvious and journalist friends will understand what they are.

As far as the sticks are concerned, first an attempt was made to separate prestigious editors from their newspapers. Then, an attack was mounted on “press barons” and the “jute press”, “monopolists” and all the other choice expressions of an era which I hope is past. By the middle of 1971, it was thought that the process of pulverization and intimidation had been advanced sufficiently for the Government to come forward with a measure to put the entire Indian Press into a strait-jacket. Briefly, if this plan had succeeded – and this was brought about with the direct participation of two Cabinet Ministers – it would have denied managements the right to manage, denied owners the fruits of ownership, and, most important, denied editors the right to edit. To illustrate: editors would not have been able to edit because one of the provisions of this scheme was that the editor of a newspaper would be elected every year by the working journalists in that organisation. In other words, the editor would be in a perpetual popularity contest with his staff and any sort of discipline, let alone teamwork, would be impossible. Mercifully, this scheme was abandoned under pressure and largely from “The Statesman”, because we were the first to expose this nefarious scheme.

Thereafter, various other devices were adopted. Control of advertising rates by the Government and the exploitation of Government advertising as a form of patronage; a monopoly of newsprint, brought into being so that every newspaper in the country would have to make pilgrimages to Delhi to beg and borrow newsprint on which to print their newspapers. For all these reasons, I am driven to the conclusion that by the middle of 1975, the Press was in no position to stand up and fight. And the Press did deserve the taunt’s that our new Minister for Information hurled at them when he said that “when you were only asked to bend, you chose to crawl.” He was right. This did happen. He also said that, “You did not even attempt to rattle your chains, let alone try to break them.”

****

I would like to say that wherever freedom is threatened and liberty infringed, it is the duty as well as the privilege of all men of goodwill to stand up and be counted, and to make as big a noise about it as they can, because this tends to intimidate the oppressors.

It is important to realise that basic Human Rights are basic to all men. This is a worldwide acceptance or there should be a worldwide acceptance of this. I have referred to the London Times with approval. I must also criticise very severely what they said in 1971 in an editorial entitled ‘Freedom of the Press in Asia’–“No one can expect true press freedoms to be enjoyed in countries still so young in their independence.” The horrible condescension apart, I do not think it is possible to urge that when basic Human Rights are involved, some are less basic than others. Consequently, there is no relationship between economic advancement and Human Rights, although it has been the objective of tyrants and despots of all hues and persuasions to attempt to make the former dependent on the absence of the latter. In other words, the suggestion is that economic advancement is not possible unless there are borne curbs on liberty. No one has shown to our satisfaction that there is any such relationship. In fact, the verdict of the Indian people has been categorical in the opposite direction. “The Economist” said it very well when, in examining the Indian scene after the Lok Sabha elections, it came to the conclusion that “no one will ever be able to claim again that there is a choice between freedom and bread”. This is so true. I suggest a proper reading of history shows that bread and freedom go together and the pursuit of liberty must continue.

There is a need in our time to reaffirm the role of the Press in this country. It is necessary throughout the free world for the Press to re-assess its role and assert very boldly, not apologetically, what a free Press is all about. It is no part of the duty of the Press’ to pay any heed to the sensitivities of governments. Our duty is to our own high code of ethics (not the bogus one that the previous government chose to impose upon us) )–to report objectively, to analyse logically and to criticise fearlessly but always with an ear to the voice ,of dissent, which is the one unfailing test of respect for Human Rights. As the great scientist, G. H. Hardy, once said, “It is never worth a first class man’s while to express a majority opinion; by definition there are plenty of others to do that.”

To access the complete, unabridged piece, click here. Visit indianliberals.in for more works by Indian Liberals dating back to the 19th Century.

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.