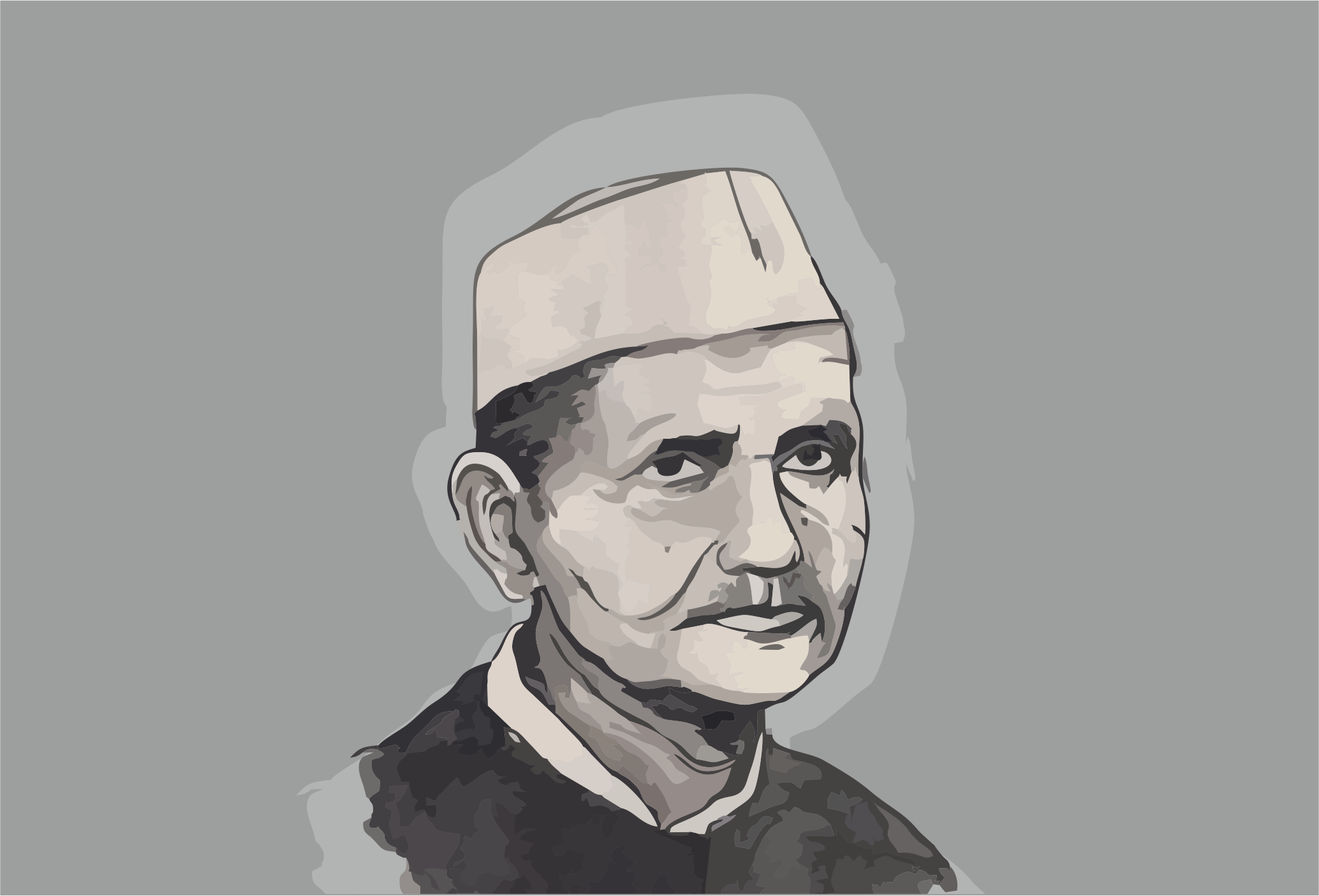

The promising but short-lived career of significant political actors often makes for interesting what-if scenarios for historians. Certain specific cases would include the assassination of John F Kennedy, the death of Sardar Patel in 1950, the decline of Swatantra Party after Rajaji, and short-lived Prime Ministerial tenure of Lal Bahadur Shastri. In Shastri’s case, he himself had accurately predicted the what-if scenario in a conversation with the journalist Kuldip Nayar. In response to Nayar’s “After Shastri Who?” question, Shastri had responded, “If I was to die within one or two years, your prime minister would be Indira Gandhi, but if I live three or four years, Y.B. Chavan will be the prime minister.” A further attempt at such counterfactuals has been made by the historian Ramachandra Guha. He has argued that had Shastri continued as India’s Prime Minister, the economic history of India would have turned out differently. Shastri’s speeches in 1965 were signalling a shift from the Nehruvian socialist agenda.

Shastri was no socialist despite his 1964 proclamation in Parliament that “socialism is our objective.” Himself a poor father who lost his girl child to an illness, his beliefs informing the policy approach stemmed from personal empathy with the poor. In this sense, he wasn’t ideologically wedded to socialism like Nehru. On the contrary, he was pragmatic like Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi. Shastri’s pragmatism in economic matters meant a move away from socialism to market. Indira’s political pragmatism, in contrast, made her an ally of the left. Also, the lack of any formal economic training or prior experience of planning made Shastri more amenable to the outside opinion. In this and more, Shastri resembled the other reformer Prime Minister, P V Narasimha Rao.

Like Rao, Shastri was also no reformer by conviction. He was responding primarily to the worsened economic situation and as is the case of the Indian political economy, reforms accompanied every crisis of statist socialism. It is in this way that both Shastri and Rao scripted liberalization saga, the latter more successfully than the former. In line with his grounded upbringing, Shastri had a Gandhian approach towards economics with a focus on small and quick projects with less expenditure. But like Rao, when confronted with the crisis, he turned a reformer. In Shastri’s political economy, food shortage would be tackled by shifting the investment to agriculture; the solution to black-market lay in incentives, not coercion; inefficiency of PSUs entailed shift to the private sector; and import substitute needed substitution by export promotion.

By the time Shastri took over as PM, the failure of the third Five-Year Plan was clear. Growth in national income barely kept pace with population growth, the prices rose substantially, and food grain became scarce. The very brief tenure of Shastri would see him tackling the food grain crisis and in the process, sowing the seeds of the Green Revolution. But before that came the dwarfing of the Planning Commission. Initially conceived as an advisory body, the imperative of Nehruvian statism had turned the Commission into a centralized institution. Earlier, Nehru’s Finance Minister John Mathai had resigned in protest against the formation of the Commission. Mathai saw it as an extra-constitutional body turning into a parallel cabinet. Shastri changed the appointment scheme for the Commission based on indefinite tenure to fixed contracts. He also instituted a parallel body called National Development Council in 1964 to get policy insight from experts, economists and scientists included. Also, unlike Nehru who deliberated with stakeholders in the Planning Commission meetings, Shastri would meet them on an individual basis.

In response to economic stagnation, Shastri was clearly doing away with many of the Nehruvian-era practices. Nowhere was it clearer than the shift in priority for the fourth Five-Year Plan. Shastri wanted to promote agrarian growth in contrast to the earlier focus on heavy industries. After a surprising night phone call from Shastri, the technocrat minister C Subramaniam was brought to the Food and Agriculture Ministry. Subramaniam would go on to promote the private sector, technological innovation, and foreign investment amidst a hostile leftist consensus. The food grain crisis soon saw the playing out of the ideological divide. The PM and cabinet blamed hoarding for the crisis and by extension, vouched for price control and state trading in food grains. Subramaniam proposed the market-oriented approach to increase production. He favoured the price incentive to private actors and the usage of chemical fertilizers as policy measures. Subsequently, the L K Jha Committee was established to look into the matter. It endorsed Subramaniam’s measures. Based on the committee recommendations, Subramaniam went on to set up the Food Corporation of India in 1964. FCI, at that time, wasn’t dependent on price control and compulsory procurement but competed with private traders in the open market.

The World Bank report by Bernard Bell based on his September 1964 visit to India further provided the impetus for the reform agenda. After the 1965 India-Pakistan war, Subramaniam came up with a three-pronged plan to improve the agrarian economy. He advocated the use of High Yielding Variety seeds, price incentives to farmers and focused use of improved farming inputs into irrigated areas. Subramaniam’s capitalist blueprint and maverick technocracy would lead to Green Revolution, making India self-sufficient in food grains.

This shift from social to technological reform in agriculture, however, didn’t go down well with the leftists and bureaucrats. Subramaniam was accused of pushing the agenda of market-liberal C Rajagopalachari presumably because he was part of the Rajaji’s Madras cabinet in 1952. The opposition to capitalism in agriculture was also based on the argument that technological innovation would only benefit big farmers. The leftist critique of capitalist farming, however, didn’t contend with the scale-neutral effect of technology, benefitting both small and large farmers in proportion to their holdings. The usual charge of “sell-out to the US” was also hurled because of the involvement of both the Ford and Rockefeller foundation. The leftist critique of the Green Revolution ironically didn’t realize the continued dependence on humiliating foreign aid entailing in absence of productivity improvement due to technological innovation. The Green Revolution brought by modern seeds verities and technical innovations enabled the sustained annual growth rate of 5.5 percent in wheat production during 1966-77.

In line with the World Bank report, Shastri also contemplated devaluation of the currency to promote exports. His Finance Minister T T Krishnamachari was staunchly opposed to the move but had to resign due to corruption charges. According to B K Nehru, Subramaniam and other ministers had convinced Shastri to go for the devaluation move. Later in 1966, Indira Gandhi devalued the currency only to find that the promised non-project aid from IMF didn’t materialize. I G Patel called it ‘the great betrayal’. Shastri’s reformist credential further gets bolstered by the fact that he entrusted the principal secretary L K Jha to chart out a strategy for liberalization. Gurcharan Das has mentioned in India Unbound the news coverage of the upcoming liberalization move in early December 1965. The veracity of the story was confirmed by L K Jha to Ashok Nehru. The liberalisation plan, however, didn’t come to fruition due to the sudden death of Shastri in Tashkent. The rest, as they say, is history which basically amounts to India waiting for the next reformer till 1991.

Author’s Note: I would like to acknowledge the contribution of Amit Kapoor and Chirag Yadav, author of the book The Age of Awakening. Kapoor and Yadav have called Shastri “the first reformer”. This piece, in part, draws upon their analysis of Shastri years.

Indian Liberals is an open, multilingual digital archive committed to preserving liberal voices in the Indian public sphere.

Visit indianliberals.in for more works by Indian Liberals dating back to the 19th century.

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.