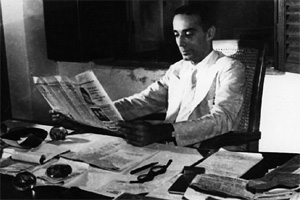

The following text is an excerpt from a speech delivered by M R Masani in 1965. M R Masani was one of the most prominent Indian liberals–he was a part of the Constituent Assembly that drafted the constitution; and was closely associated with the Swatantra Party.

Let us now examine the widespread assumption that we in this country can sustain democratic government alongside of a State monopoly of economic ownership of industry, trade and agriculture.

First let us consider the effects of such a situation on the lives of the worker, the peasant, the investor and the consumer and the man in charge of industrial production. Today, the worker has a right to choose and change his job within the limits of his training and capacity. He can withhold or deny his labour, participate in collective bargaining and, if need be, strike work together with his comrades. If he should lose his job or the strike should fail; he finds other enterprises ready to employ him. In society where the State is the only employer and every citizen willy-nilly a State employee, to what extent will these precious rights be preserved? Is there any reason to believe that, when there is only one employing authority in the country, it will permit an employee throw up his job in an economic activity where he is performing a necessary function and allow him to shift at will to some other occupation? Is it likely that a State, exercising a monopoly of production and distribution, will permit its employees to go on strike and thus upset the National Plan?

Or let us take the peasant. Once he is a member of a collective farm or, for the matter of that, of a co-operative farm–the terminology will not make very much difference–is it to be expected that when he finds that the co-operative farm does not suit him and he wishes to withdraw from it, the original plot of land which he was persuaded to surrender will be restored to him and he will be allowed to go his own way?

As for the small investor who survives, his freedom of choice will, be restricted to one of two or more issues of a so-called ‘voluntary’ State Bond to which he will be forced to subscribe. His plight may best be imagined from the report that has just come out from Czechoslovakia, about the finding of’ an unidentified corpse. The police report said: “Aside from two Government Bonds, no other signs of violence were discovered on the body.”

In a free economy, it has rightly been said, the consumer is king. The consumer who today is, within the limits of his income, able to exercise a wide freedom of choice about how much he shall spend, on what he shall spend, and how much he shall save will then be faced with one universal seller from whom he must obtain all his wants. The range of goods offered to him will be decided and the price fixed by the State trading monopoly. If the quality or the price do not appeal to him, there will be no other brand of goods to turn to. To meet his basic needs, he must purchase or perish.

Today, thanks to the law of the market–the law of supply and demand–and the discipline of the balance-sheet, it is the consumer who decides for the entrepreneur ‘whether’ to produce and ‘what’ to produce. When a man buys something on the free market, he is casting his vote as a citizen of the national economy. He exercises a free choice which, by affecting the price, influences a decision as to how the economy shall be directed.

To access the complete piece, click here. Visit indianliberals.in for more works by Indian Liberals dating back to the 19th Century.

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.