In July 2016, the government notified the inclusion of stents in the National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM), citing irrational and exorbitant prices. In the notification, dated 13th February 2017, the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA) observed:

“As whereas the Government is under constitutional obligation to provide fair, reasonable and affordable price for Coronary Stents and therefore its immediate intervention is imperative to check unethical profiteering and exploitative pricing; and whereas Paragraph 19 of the DPCO, 2013 inter-alia authorizes the government, in extraordinary circumstances, if it considers necessary to do in a public interest, to fix the ceiling price or retail price of any drug for such period, as it deems fit.”

Choice, innovation and a market driven by competition is the bête noire of a government determined to create hurdles instead of helping new firms manufacture better and affordable products by easing the process of obtaining permits to set up a business.

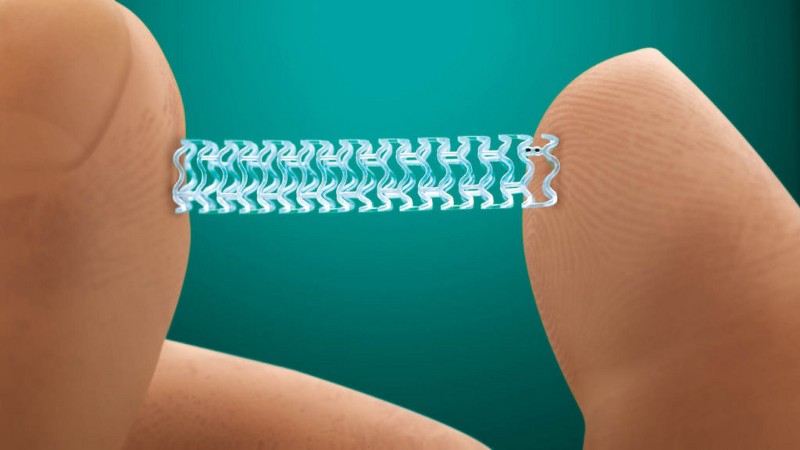

A coronary stent is a tiny wire mesh tube that is placed inside an artery in order to remove any blockages and widen it so that blood flow is uninterrupted. It is also used to support weak arteries which have difficulty in maintaining blood flow. Stents that are not coated with drugs are called bare metal stents. There is another category of stents which elute an anti-proliferative drug to prevent cell proliferation — known as “medicated stents” or drug eluting stents (DES). Both are widely used.

The government’s defense of a cap on stent prices is that charging patients in an “unethical” manner is wrong and hence, keeping in view the essentiality of stents in a country where there are approximately 30 million heart patients and 2 lakh heart surgeries taking every year, it is the binding responsibility of the government to serve the common people. According to WHO statistics, ischemic heart disease was the leading cause of death in India, killing over 1.2 million people in 2012. This number has increased since then — 53% increase from 2005 to 2016 according to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data published in the Lancet this year.

A price control is not a permanent solution to the problem of high prices. It reflects a government’s failure to address the long-term market issues — factors which impede the growth of businesses and markets. If promoted in an effective manner, the stent market in India has the potential to outperform the largest stent makers of US and Europe. “Indian Coronary Stent and Angioplasty Market through 2020”, a market report published by ABMRG (Ace Business and Market Research Group) in 2015 states that the stent market in India was valued above $400 million in 2012. The report further says that this market would triple by 2021.

The problem is not that the costs of stents outside India are skyrocketing. Price disparity remains abysmally high. The estimated average landed cost of an imported drug eluting stent (DES) is only Rs.17,000 while that of a bare metal stent (BMS) is between Rs.5000–7000.

So, why are we paying so high?

It has more to do with the supply chain — firstly the MNCs which import stents make a profit, secondly the distributors make their own profit, and finally hospitals also push in their profits. Sometimes this profit margin is three to four times the landed cost of the stent. This kind of middleman money-making is the reason for us paying such exorbitant prices for life-saving stents. It is the same for food items whose costs swell as they go through one middleman to the next. Cutting down on the intermediaries will reduce costs significantly. Other reasons for the high cost of stents include maintaining an inventory of stents in hospitals even when a few stents are used per day and a doctor-distributor nexus wherein distributors pay doctors for recommending stents to patients who don’t really need them.

How to address this issue?

Make the supply chain fluid, ease restrictions on trade, facilitate logistics by improving infrastructure, penalize private hospitals forcing patients to purchase stents from their own stores at high prices, promote competition in domestic stent-making market by increasing access to credit, and make it mandatory for hospitals to make information about stent availability/cost public.

Also, information dissemination about stent types and usage can help patients make informed decisions. Many of us who enter hospitals or clinics do not even have the faintest idea about the type of medication the doctor recommends. As we make a transition towards a post-industrial society, the fact that we remain so unaware about important things around us is the biggest problem besetting our lives today. In a service-based society, knowledge is a valuable tool. The decision about who needs a stent and who doesn’t must be based on specific guidelines — the knowledge of which should be easily available.

Recently the government of Maharashtra drafted a bill (Prevention of Cut Practice in Healthcare Services Act, 2017) to stop the practice of kickbacks in medical networks — commissions, cuts and gifts received by doctors, pharma companies, labs, maternity homes, clinics, and dispensaries in exchange for referrals. The decision of whether a patient needs a stent or not — and what kind of stent is good enough to do the job should be rationally justified. A ban on commissions or a cap on prices will not yield results. Doctors will find alternate ways of receiving their cuts and distributors will dig up other routes to sell stents at their own prices. It is only through obtaining prior knowledge and making informed choices can things be driven in the right direction.

Capping the price of stents subsidizes the rich who can afford expensive stents.

A supposedly all-inclusive measure as this will indirectly subsidize the rich who could otherwise afford to buy stents at high prices anyway. There are patients who fly in and out of India for angioplasty and stenting. They are willing to pay high prices for high-quality stents. Because of this cap, high quality stents may lose disappear from our market altogether. It will badly impact our medical tourism and companies will cut down on further research and innovation.

Abbots Healthcare announced the withdrawal of two of its latest generation coronary stents from India, including a bio-absorbable stent it had introduced four years ago, citing commercial unviability. It got the permission to withdraw its premium metallic stent, Xience Alpine in September this year.

The worse is yet to come. In the words of Milton Friedman,

“Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.”

Instead of price control, the government should have addressed the barriers to competition in the coronary stent market.

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.