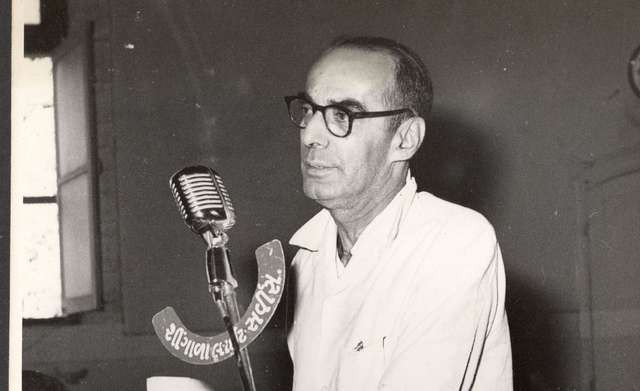

The subject of the Federal Structure and States’ Rights is one in which my interest dates back to my membership of the Constituent Assembly and its Committees. As it happens, I was a member of the Committee appointed on 24th January, 1947, on a motion by Rajaji to examine the scope and content of the subjects that should be allotted to the Centre, which came to be known as the Union Powers Committee. There were twelve members, with Jawaharlal Nehru as Chairman, and Mr. Sarat Chandra Bose, Dr. Pattabhi Sitaramayya, Pandit Govind Ballabh Pant, Sir N Gopalaswamy Iyengar, and Dr. K. M. Munshi among my fellow members.

It was in this committee that perhaps for the very first time an issue which was later to develop into one of the major dividing lines in Indian politics came up in a small way. I recall a significant passage at arms that took place between Pandit Nehru, our Chairman and myself, when Jawaharlal Nehru asked for the expression of members’ views as to which list planning should be placed in. I promptly answered that it should be in the States’ List. Nehru glared at me and said he entirely disagreed and that it should be placed in the Union List. This was to be the firist of many debates he and I were to have about the nature of Planning since he believed in Soviet style comprehensive planning and I stood for the Gandhian concept of a decentralized economy. Naturally, Jawaharlal won and the subject of “Economic and Social Planning “ was placed in the Concurrent List covering matters in regard to which both the Union and the States could legislate. The Report of our Committee observed: “ We have included planning in the above list for the reason that although authority may rest in respect of different subjects with the units, it is obviously in their interest to have a co-ordinating machinery to assist them “.

The States’ List includes three important entries, namely Industry, Trade and Commerce, and the production, supply and distribution of goods. On the other hand, the Union List included “industries declared by Parliament by law to be necessary ‘for the purpose of defense or for the prosecution of war” and “industries the control of which by the Union if declared by Parliament by law to be expedient in the public interest.” The way in which this allocation of subjects has worked has unfortunately upset the balance of` the Federal Constitution. Not only did Parliament enact the Industries (Development and Regulation) Act in 1951 specifying the list of industries which should be controlled by the Centre but in the course of time more and more industries were added to the list and, for all practical purposes, the subject of Industries has been virtually shifted from the States List to the Union List. The Annual Survey of Industries shows that, in so far as under takings with a fixed capital of Rs. 2.5 million and over are concerned, the Centre has now asserted its control over as many as ninety-three per cent of these industries as computed by the value of their output. It has been sarcastically pointed out that Parliament has used its power to hold that the public interest demands that it should control the production of articles of such vital and strategic importance as razor blades, gum, shoes, cosmetics, soaps and other toilet requisites!

Can there be any doubt that a fraud has been perpetrated on the Constitution? The existence in Delhi of full-fledged Ministries For Education, Agriculture, Industry, Labour and Home Affairs despite these subjects being in the States List, has over the years contributed to the erosion of the autonomy of the States and made them little more than glorified Municipalities or Local District Boards. Yet another example of this trend is the manner in which the Centre has monopolized the media of mass communication. All India Radio, which should really be a public service at the disposal of the Union Government, State Governments, voluntary associations and the public at large, is run departmentally by a Ministry of the Union Government. The only way in which the rights of the States could be asserted and these important means of communication freed from the dominance of the Centre would be to give effect to the recommendation of the Chanda Committee that the Radio and Television Services should be placed in charge of autonomous statutory Corporations like the B. B- C. and I. T. A. in the United Kingdom.

In so far as the Planning Commission is concerned, a Seminar which met in Agra from la/Iarch 24 to 26, 1972, under the auspices of the Leslie Sawhney Programme of Training for Democracy, at which I happened to be present, had an interesting proposal to make: “ In the course of discussion on the economic aspect of federalism, the role of the Planning Commission came up. It was agreed that the Planning Commission should be an expert independent statutory body, acting in an advisory capacity, and should consist of experienced men from public life, industry and trade unions and administration. Apart from preparing a national plan in certain specified areas, its role and scope should also include the indication of priorities and the co-ordination and integration of the State plans into a national plan. Initiation and formulation of detailed planning should, however, be on a multi-tier system at the State, metropolitan and district levels. The discussion on the development of backward regions led to the conclusion that, where possible, there should be regional planning for backward regions in a State.

The Constitution when it was framed established what might be described as a tight Federation with less autonomy for the States than in most federal constitutions of the world such as those of the U.S.A., Australia and Switzerland. If there is any one country that needs a federal structure more than others, it is India with its size, population and wide diversities of race, religion, and caste and ways of life. Even the maintenance of a free and plural society cannot be assured in such conditions except on the basis of genuine federalism

Already the concentration of power in a few hands in Delhi has contributed towards the erosion of our democracy and democratic institutions and threatens to end up, as in Bangladesh in a one-party authoritarian rule.

On the other hand, one has to take note of a growing sense of alienation from the Centre which is stronger in some States like Kashmir, Nagaland and Tamil Nod than in others. This alienation has historical and economic aspects. Regional aspirations as also linguistic and other tensions are real. They cannot be wished away. They need to be handled with sympathy, understanding and imagination. I am convinced no amendment of the present Constitution is called for since it is not the Constitution that is defective. On this point I find myself in agreement with the Administrative Reforms Commission. All that is required is an acceptance of appropriate conventions and a respect for the spirit and the letter of the Constitution. There is ample scope within the Constitution for sound federalism provided there is a continuing process of consultation with States; the Centre scrupulously avoids any suspicion of partisanship and political motivation in dealing with a particular State and a continuous search is made for procedures and modes of associating the States with the decision-making processes of the Union.

Further writings of Minoo Masani can be accessed at the Indian Liberals open, digital archive.

Read about impacts of GST on Indian Federalism: https://spontaneousorder.in/gst-federalism/

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.