Mochi: Kishore Kainth

Kishore Kainth, 28-years-old, is a third-generation cobbler. He studied until 8th grade in a government school in Harla village in Nawadah district of Bihar. Kishore took to the profession at age sixteen to support his widowed mother after they were driven out of their home by his older step-brothers. He worked as a daily wage landless labourer on farms before returning to his family profession. Through his childhood, he assisted other men in his family as they prepared the leather, stitched new shoes, and repaired old ones to give them a new lease on life. Therefore, being a cobbler came easily to him. He made anywhere between ₹20 and ₹50 a day. However, after his marriage and the birth of two children, the daily earnings were not enough to support his family. In 2012, his wife fell seriously ill after the birth of their second son. He had no health insurance and needed money. Kishore took a ₹35,000 loan from a local moneylender at 2% simple interest per month. After signing the documents, he alleges that he was given only ₹20,000. He tried to reason with the lender, but the conversations turned ugly. The regular violent threats by goons demanding the monthly interest of ₹700 were too much for him to bear. He found support from folks in his community who had migrated to the cities and made annual visits home. Their warning resonated with him. “You will work like a donkey here and become a donkey.” And the simple math made sense. “In Harla, I got ₹2 to mend a sandal and ₹4 for a shoe. In a city, I could get ₹8 or more.” In late 2013, leaving behind his wife and two young children in the village, he took a train to Delhi with few clothes and his wooden shoe-toolbox. He lives with five men from his village, all cobblers. They share a tiny single room in a slum, and his part of the current rent is ₹600. This has been his home since then.

In the initial days, he would start his day at 9 am, carrying his tools in the wooden box, all weighing nearly 8 kg, in search of customers. He would station himself outside a local school, at a bus stand, near a tea stall, or outside a popular restaurant waiting for customers until he was shooed away. Eventually, he found a permanent spot on a busy main street of a ‘commercialized’ residential neighbourhood. A cobbler who usually sat there had gone home to his village and never returned. Kishore took the spot that was “meant to be” his. This has been his “post” for the past three years. He pays no rent for the space on which he makes a seat of two mats for himself; over time, his small wooden toolbox was replaced by a larger metal chest. He has created a roof from remnants of a plastic sheet supported by wires and tree branches. It protects him from the sun and rain during his 10-hour shift all seven days a week.

He described to me his typical day as follows. Every morning he starts by sweeping the area and sprinkling water to settle the dust. He unlocks the metal box, and creatively arranges the ‘aidan’ (cast iron shoe anvil), ‘tota’ (pliers), ‘pakkad’ (pincers), ‘kenchi’ (scissors), ‘hathodi’ (hammer), ‘sooaa’ (awl), ‘sui’ (needles), ‘gond’ (glue), ‘kattar’ (shears to cut leather), ‘keel’ (small nails), ‘chamda’ (leather pieces), brushes, polishes, and some rags on his workstation. Shoelaces, ‘dora’ (strong, waxed thread), and rubber soles are hung on the back wall for easy access. Then he lights an incense stick and says his prayers in silence. With sad resignation in his voice, he told me that the wall was once far more decorative and cheerful. “I had pictures of my Gods on the wall. I would offer flowers and water every morning. Then ‘they’ came and told me to take the frames down. Apparently, God and shoes don’t go together.” I asked him who ‘they’ were. He simply shrugged his shoulders.

Spending time at his ‘shop’, I realized most of his day passed waiting for customers. On an average day, he made ₹200, charging ₹8 for repairing slippers, ₹15 for mending shoes, ₹25 for changing soles, ₹30 or more for fixing canvas bags, and ₹75 for patching a leather bag. The rates were higher for fancy footwear as “they need more care.” Kishore’s bonanza came on weekends when he polished at least 10 pairs of black leather school shoes for ₹15 each. He opined, “Times have changed. Schools are strict about proper uniform and expect students to wear polished shoes. That’s good for my business. But at the same time, people do not want to bother getting shoes repaired. They do not mind throwing away a bruised pair and buying a new one.”

Despite the harsh circumstances, Kishore considered himself blessed. Strangely, he found solace in the fact that since 2012 he had never felt the need to borrow again from a moneylender. Kishore did not foresee the possibility of paying back the loan of ₹35,000. He estimated that he had paid more than ₹50,000 as interest on the principal. However, his main worries were centered on the future of his two sons. His parting remarks to me were despondent with a tinge of suppressed hope. He said, “Things will probably never change. My children will not see a better life than mine. Luckily, they will not be cobblers, as they are not with me to watch and learn the craft. I am willing to do whatever it takes to improve their life. If only, somebody would show me the way.”

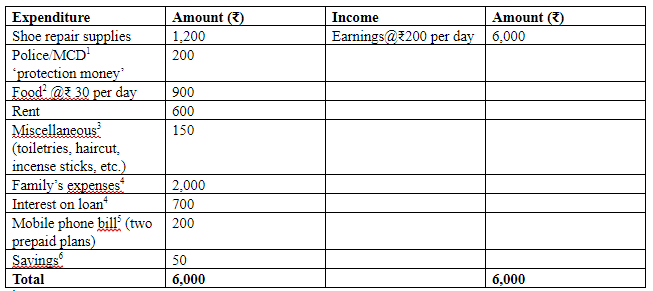

Kishore Kainth’s monthly income-expenditure account:

1MCD is Municipal Corporation of Delhi. It is responsible for maintaining clean streets and providing civic amenities in Delhi.

2Kishore makes eight chappatis in the morning. He eats two in the morning with tomato-onion ‘churi’ and eats three chappatis with ‘channa-aloo’ gravy (bought from a roadside stand) for lunch and dinner. A plate of channa-aloo gravy costs him ₹6.00 each. Kishore drinks tea in the morning and late afternoon. Each is sold in a small paper cup for ₹4.

3He has not bought clothes or shoes for himself in the past two years.

4He sends cash home to his wife every couple months with any known, reliable acquaintance traveling from Delhi to Nawadah district, Bihar. His wife uses the money to run the house, provide for their two sons aged 8 and 6 years and pay interest of ₹700 on the outstanding loan. She lives rent-free with her parents. The boys attend a government school where tuition, books, and uniform are free.

5He has two pre-paid mobile phone plans, one for his wife and the other for himself.

6Each year, he spends 30 to 45 days in his village. His savings are drawn down during this period. To ‘fund his vacation’ he does odd jobs in the village. Occasionally, Kishore borrows from and lends to his roommates on interest-free, short-term basis.

*Name and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of the individual.

Read more: https://spontaneousorder.in/uncertain-lives-how-street-vendors-earn-spend-and-borrow-part-3/

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.