Subziwallahs: Pandey Brothers

The Pandey brothers – Mahesh (33) and Ajay (27) – run a vegetable and fruit stall in Delhi. The earnings from their business support their joint family of twelve members that includes their respective wives and five children, elderly parents, and a nephew.

Mahesh left home in Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh at age 16 to work for his uncle in Sahibabad Mandi,a busy wholesale vegetable market in Ghaziabad. His uncle ran a small business renting out tempos (mini trucks) to vegetable vendors to carry their daily bulk purchases from the mandi to neighbouring areas. Mahesh was his uncle’s driver, mechanic, loader, negotiator, and money-collector.

Inspired by Mahesh’s financial independence, a few years later Ajay left their hometown to work alongside his brother. The mandi became their home and work place. They slept, ate, and worked amidst hundreds of labourers in the sheds, where lacs of rupees were exchanged for farm produce from across the country. Not content with earning a fixed monthly salary, the two decided to start their own business – buying fresh fruits and vegetables from the mandi and selling it on a four-wheel pushcart in residential lanes and by-lanes of a neighbourhood in Delhi. They would work 10-hour days, walking the streets, calling out to housewives to buy their “taazisubzi” (fresh vegetables). That was fourteen years ago. Since then, the brothers have married, had children, bought a three-room apartment and settled down in East Delhi with their parents. They continue to buy fruits and vegetables from Sahibabad Mandi, except instead of selling on mobile carts, they have a rent-free, twelve feet by seven feet roadside stall,fitted with a beachside umbrella,in the same residential neighbourhood where they pushed their cart.

The day begins at 4 am for Ajay, and his 22 year-old nephew, Sushant. They reach the wholesale market at 5 am on their motorcycle. Based on previous day sales, they decide what and how much they need to buy. Walking around, they look for the best quality and price. On a typical morning, they buy 200 kg of fruits and vegetables spending not more than ₹10,000.

Unlike big traders with large purchase orders, the Pandeys cannot participate in auctions, get discounts, credit or access to ‘first’ quality goods. They pay cash and buy at fixed prices decided by commission agents at the mandi.

After their shopping is done, they sort, pack, and load their stock onto a rented tempo. It is 7 am when Ajay and Sushant finally leave the mandi.Mahesh, being the older brother, gets the privilege to sleep in late and arrive directly at the stall at 7 am in his Maruti 800(a small car) with the unsold inventory of the previous day. While waiting for the day’s supplies, he sweeps and dusts the space, setsup tables with the wooden planks and plastic crates that are stored overnight in a nearby garage, and puts a plastic sheet as a table cover. He sorts through the ‘old’ stock, culling what cannot be sold.

The loaded tempo reaches the stall a little after 8 am. Sacks and boxes are unloaded and the contents neatly arranged in a specific order. The team understands that customers will not pay well for produce that looks tired, unappealing,or off-colour. Over the years, they have developed a keen sense of styling. Greens, in their multiple shades, are stacked on one side. Spherical lemons and tomatoes are heaped in tilted round trays with edges that prevent them from rolling over. Cabbage heads are posed atop each other in a pyramid while carrots and radish are arranged in a neat spiral pattern. Hardier vegetables are kept in front, onions in a gunny bag on the ground, and potatoes, the bestselling item, have a separate table for display. It takes the three men an hour to create this visual treat.

Most importantly, the Pandeys follow a long-held family superstition: never place measurement gear on an empty table. Thus, the weights and weighing balance are brought out last. Their busiest time is from 9 am to 12 pm and then from 5pm to 8 pm. This is when their customers –the memsahibs(upper-class ladies), their cooks, and helpers come looking for freshest fruits and vegetables. On an average day, they sell 80% of the inventory and make a profit of ₹3000, all in cash. Their earnings change with seasons. Mahesh, the accountant of the family,explains the reasons for higher profits in winters than during summers and monsoons. He says, “Mandi prices fall in winter as supply increases and spoilage decreases. Also, people eat and buy more in winters boosting our sales. Moreover, many street vendors leave the city because of a steep dip in temperature. This reduces competition. All this means higher sales and profits for us in the cold months.”

Irrespective of seasons, their daily routine never eases up. The stall is open for business seven days a week, including holidays. The city’s extreme weather makes it worse. All day in the outdoors they are exposed to the hot and dry winds in the summer, oppressive heat and heavy downpour in the monsoonand the cold waves in the winter. Oddly, it is not the weather, but the callousness of the customers in recent years that they find most challenging and disheartening.

Maheshpartly blames online shopping for change in customer attitudes and behavior. “Because of Bigbasket and Amazon, several customers make us feel that we are dispensable and they are doing a favour by shopping with us. Would Bigbasket allow a shopperto bend and snap each ladyfinger’s tip to check for its crunchiness and return those that fail her test?” he asks me testily. “It is easier to accept predictable harassment from policemen, MCD workers, and local thugs than the thoughtless behaviour of some of our patrons.” He continues, “Our responsibility is to get from the mandi and bring it to your doorsteps. Quality of our produce is a pact between nature and the farmer. So when a memsahib complains thatthe apples are too red, and yet not sweet, it’s not our doing.”

Then there are customers who take advantage of the fact that they are ‘regulars.’ They pick vegetables when they are passing-by without paying for it. They make excuses like, “I am not carrying my wallet. I will pay later, add it my hisaab (account).” The ‘later’ is never specified, and the account is kept ongoing. “We get no credit from our suppliers and yet to maintain goodwill we are forced to offer it to our customers,” complains Sushant.

Sushant finds the customers who argue endlessly over prices even more tiresome. “It’s easy to tell their type. They come in fancy cars and demand petty discounts. For everything, they moan that the price is too high. We have smartened up. We quote them a higher initial price and then allow a discount to make them feel good about their negotiating skills.” Selling perishable items creates a further disadvantage. “It’s not that we can refuse to sell. At the end of the day, unsold inventory is a loss for us. There is only so much that we can carry forward the next day or consume ourselves,” says Sushant with a sense of helplessness.

However, more than the monetary loss, it is the lack of acknowledgment of their sincere efforts that pains them. Rajesh, the quietest of the three, puts things in perspective, “We sell good quality, desi(homegrown) produce at low prices. We follow all rules – no plastic bags, keep the pavement clean, have a license, do not beg or steal; yet the authorities and some customers view us as tricksters.”

Through the day, their keen eyes scan their display, removing wilting pieces, spraying water on green leafy vegetables, covering delicate ones with a damp gunny cloth; taking care, so that customers eat healthy.

At times they wonder if it’s worth it. Sadly, in their case, they feel they have no alternative.

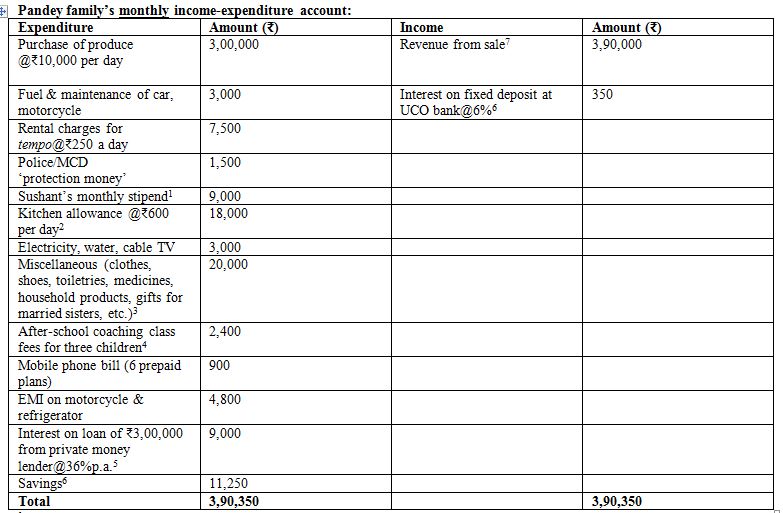

1Sushant is their sister’s son. He lives with his uncles and helps run their business. He receives a stipend of ₹9,000, in addition to free boarding.

2Their wives are given an allowance of ₹600 a day to run the kitchen. Vegetables and fruits are used from unsold inventory. The family consumes 4 litres of milk and 1.5 kg of rice daily. Mahesh carries lunch for his team when he leaves home at 7 am. Often, the family has house guests from the village who stay with the Pandeys for an extended period of time.

3Both parents are elderly and have multiple health issues. Their monthly medicines and doctor’s visits average ₹3,000. There are five children in the joint family. The elders buy new clothes for the children on their birthdays, Diwali, weddings, etc. from an annual budget of ₹3,000 per child. The Pandeys have three married sisters.

4Children attend free government school. The school provides books, uniform, and shoes. The older three children go to private coaching classes after school.

5The family took a loan for home improvement and purchase of a pre-owned car in 2016. They plan to repay the outstanding loan by December 2020.

6Mahesh handles all financial matters. Savings are deposited with UCO Bank. The family has approximately ₹70,000 in a fixed deposit scheme earning 6%p.a.

7 Based on profit of ₹3000 per day.

*Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

Part 2 : https://spontaneousorder.in/uncertain-lives-how-street-vendors-earn-spend-and-borrow-part-1-2/

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.