During the last century, Tamil Nadu has produced many political leaders, liberal scholars, constitutionalists, social reformers, and public policy thinkers of far excellence. But the quality of the last half of the century’s polity in Tamil Nadu had merely served for advancing the one’s ego on others for gaining the vote motives. This has been the case at least since 1966, involving massive indoctrination of one particular ideology and distortion of classical liberal thinkers’ thoughts.

Thoughts of some of the leading scholars on classical liberal principles were not only forgotten but perceptively neglected in all spheres of the mainstream practices. Furthermore, this era became an ideal hero-worship of political leaders without much thought about the indoctrination of the youth. The tragedy is that even after three decades of the first wave of economic reforms and free-market economic policies, the ignorance over the relevance of classical liberals’ thoughts continues.

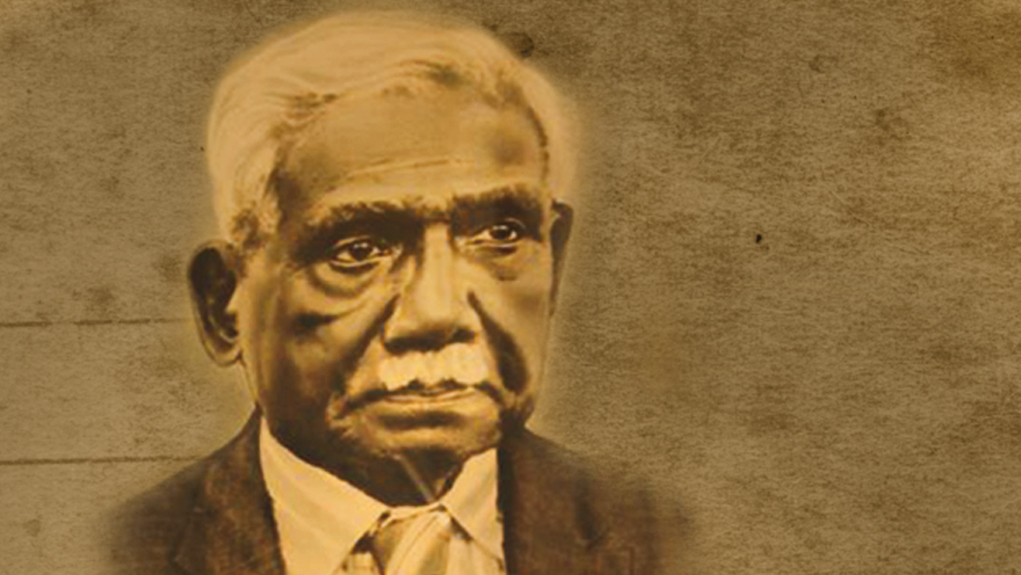

One of the great liberal scholars in recent times was Mariadas Ruthnaswamy. He was born in August 1885 at Royapuram in Madras (now Chennai) to MI Ruthnaswamy and MT Ruthnaswamy. Mariadas Ruthnaswamy was an authority on Indian history, political theory, and economics and often differed from others. Few have had such a varied and distinguished public service spanning a few decades. Ruthnaswamy was a leading educationist and professor of Indian history and politics, liberal thinker, constitutionalist, politician, parliamentarian, erudite orator, editor, administrator, and author. He was founding Vice President of Swatantra Party and represented the party form Madras State in the Upper House (Rajya Sabha) of the Parliament for two terms.

Mariadas Ruthnaswamy received school education at St. Anne’s School at Secunderabad in Andhra Pradesh, and matriculated from the St. Joseph’s College at Cuddalore in Madras Presidency (now Tamil Nadu) in 1903. He also completed his undergraduate education at Nizam’s College, Hyderabad in 1907. Thereafter, he went to England to study at Jesus College, at Oxford University and University of Cambridge and completed his History Tripos degree in 1910. At Cambridge University, he was contemporary of Jawaharlal Nehru. Simultaneously, he was enrolled for law at Gray’s Inn, London, and became a barrister in 1910. In 1911, he returned to India and was determined not to practice law despite his father’s pressure.

In 1921, Mariadas Ruthnaswamy was appointed as the first Indian Principal of Pachiyappas College, Madras (now Chennai), which was one of the leading educational institutions in the Madras Presidency. He served as Principal and also Professor for English, History, and Politics till 1927. Later, he was appointed as the first Indian to hold the post of Principal of Madras Law College in 1928 and served up to 1930. Afterward, he became the Vice-Chancellor of Annamalai University at Chidambaram in Madras Presidency from 1942 to 1948. During the period from 1930 to 1942, Mariadas Ruthnaswamy served as Member of Madras Service Commission (now TNPSC) and also chaired the Commission for some time in later years. This Commission was one of the first to be established (1929) in the country among all the Presidencies.

Mariadas Ruthnaswamy’s political career spans more than half a century. He was associated with the Justice Party in Madras since 1919, but after it was dissolved in 1944, he remained independent until he joined the Swatantra Party in 1959, founded by C Rajagopalachari among others. Mariadas Ruthnaswamy was first elected as Councillor in the Corporation of Madras in 1921 and served till 1923. And then, at the age of 40, he became Member of Madras Legislative Council and also President of the Council and served from September 1925 to November 1926. In the Council debates, he was known for his wit and quick repartee. He was a practising liberal constitutionalist, and in 1927, he was nominated as Member of the Central Legislative Assembly.

Swatantra Party nominated Mariadas Ruthnaswamy as a Member of the Rajya Sabha for two terms: first from 1962 to 1968 and second from 1968 to 1974. His speeches were eloquent and powerfully delivered in the Parliament covered a wide range of subjects lucidly and incisively. In 1968, the Government of India conferred Ruthnaswamy with the Padma Bhushan for his work in Literature and Education in Madras. This was one of the rare occasions when the leader of the opposition (Rajya Sabha) was conferred such an award. He was actively involved in activities of the Parliament and participated in all important discussions and debates as leader of the Swatantra Party.

Mariadas Ruthnaswamy was also a prolific writer, known for his erudition and knowledge of Indian history as well as many other subjects. He contributed articles regularly in the national newspapers like Sunday Standard, Statesman, and journals like Swarajya, The Week, and local newspapers like Madras Mail and Daily Express, Madras. He was editor of both English and Tamil journals publications such as Standard (1921–1923), the weekly edition of The Democrat (1950–1955), daily edition of Tamil Nadu (1951–1955) and fortnightly edition of Thondan (1972). He had published classical liberal economic ideas in The Democrat and journals like Swarajya. He was an extraordinary leader. Ruthnaswamy believed in the principles of constitutional methods and political education for achieving freedom from the British. He was against too much focus on political power and concentrated on economic freedom.

Mariadas Ruthnaswamy wrote several scholarly books published both in India and England. All in his masterly works, he explained quite vividly his in-depth thinking on the power of ideas, institutional systems, and men of characteristics that shape the institutions’ life and structure in an economy and democracy. His major works include The Political Philosophy of Mr. Gandhi (1922), The Political Theory of the Government of India (1928) – this was the first lecture under the liberal Scholar V. Srinivasa Sastri Foundation, at University of Madras, The Revision of the Constitution (1928), The Making of the States (1932), Some Influences that made the British Administrative System in India (1939), Essays in Constitution Making (1946), India from the dawn: new aspects of an old story (1949), Principles and Practice of Public Administration (1953), What Every Citizen Ought to Know (1957), Everyman’s Constitution of India (1958), Principles and Practice of Foreign Policy (1961), India after God Unknown Binding (1964), Agenda for India (1971), Legislation: Principles and Practice (1974), Violence: Cause and Cure (1969), etc. Many of these books were written with profound thinking involving comprehensive research of literature and critical examination of emerging theories like socialism, communism, collective farming, and the emergence of the state.

Even before independence, Ruthnaswamy firmly believed that economic freedom is the foremost lubricant to achieve political and social freedoms paving prosperity and equal opportunities for all. He criticised the freedom struggles movements which had focused mainly on political freedom without much thought about social reforms and economic freedom. In his article “The Techniques of Social Reforms in India” to Har Bilas Sarda’s Commemoration Volume published in 1937, Ruthnaswamy noted that “Economy in the use of energy is the surest means of ensuring success in the political as in every other kind of human effort. To turn from the political fight to work for social reform is to allow oneself to be disturbed by the siren’s call. It is to dissipate one’s energy. It is playing the enemy’s game. Social reform, however excellent at other times, is just now a nuisance. It must, therefore, get out of the way.”

And therefore, “if the attainment of political power has not been preceded by education in the social application of the ideas of liberty and equality and progress and in the will and the desire to achieve them, the mere placing of political power in the hands of the people and their representatives in the legislature and the administration will not serve the cause of social reform.” Clearly, he had warned the dominant leadership in India, which focused merely on political freedom by gimmicking the social reforms and economic freedom to centralise the power structure.

Mariadas Ruthnaswamy was against the ideas of socialism and communism, which enthralled the twentieth century. He criticized Nehruvian socialism, which led the government’s role in commanding heights of the economy. Ruthnaswamy was of the view that “Measures must be taken to improve the production of the country. This can be done not by attempting to create industries through industrial Ministries and Departments- no free state can create industries- but by establishing circumstances and conditions favourable to the production of wealth. Security of life and property, improve communications- the road systems of India is woefully defective and much of the money spent on the promotion of industry and agriculture by the state might more profitably be spent on the opening out of new roads and other communications where they are needed – the removal of all obstacles to the freedom of trade and industry within the country– these things should be attended to by the government if it wants to serve the cause of economic progress.”

Mariadas Ruthnaswamy believed in decentralised planning for the development and growth of India through devolving both political power and financial power. He was also of the view that the decentralised system of village panchayats of ancient India was destroyed by different regimes, including the British and strangling grip of India’s social customs, which also played a detrimental role. Moreover, he was a “champion of backward classes and minorities” in the broad meaning of individual liberty and equality of opportunities for all.

Throughout his life, Mariadas Ruthnaswamy championed the pivotal role of the principles of liberty, equality, and economic freedom. He was an untiring reader and authored several books wherein the assimilation of his thinking and mastery over the issues of India covering several centuries is truly mesmerizing. He was profoundly active with reading and writing even at the age of 92, days before his death in June 1977. Alas, many of his great works were consciously marginalised by propagandists even after the fact that he was a scholar from the minority community. His own community itself had treated his works as untouchable because he was a distinguished scholar and thinker of classical liberal principles.

Read more: GK Sundaram: Swatantra’s Forgotten Tamil Leader

IndianLiberals.in is an online library of all Indian liberal writings, lectures and other materials in English and other Indian regional languages. The material that has been collected so far contains liberal commentary dating from the early 19th century till the present. The portal helps preserve an often unknown but very rich Indian liberal tradition and explain the relevance of the writings in today’s context.

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.