We spent two months of Summer “inspecting” private school inspections as part of the Researching Reality Internship at the Centre for Civil Society; we came to learn that laws, much like beauty, are often skin deep. Our adventure took us all across the underbelly of Delhi including the open sewers of Mehrauli, the strangely elevated Jhandewalan and the ever so unwelcoming Shahdara. We went to seek answers from schools, principals, officials, clerks and at times even e-rickshaw drivers—all promptly shooed us away.

Our persistence, however, paid off. After 11 visits to the Directorate of Education, we obtained eight complete school inspection reports. Of the 30 officials and government school principals (who also conduct inspections), 15 agreed to talk to us.

So, why did we go through all this effort? Even though private schools are increasingly preferred by parents from all economic classes, the government continues to treat them as an afterthought rather than a co-service-provider. Moreover, operating a private school is no easy task—the government, with its large budget and free education, holds competitive stakes. Not only is the government a competitor, but it is also the rule-setter, an enforcer.

Why inspections? Inspections act as an interface, an instrument to enforce regulations, and if properly done, to improve school outcomes. However, with unclear motivations, inspections can also be used as a way to further harass the administrators at private schools.

Against this backdrop, we set out to understand the objectives, assumptions and the process of inspections. We asked: why does the government inspect? What are its objectives? How does it do it? What happens if a school fails to comply? While our upcoming paper answers these questions, this article highlights the softer aspects of our research—how different stakeholders responded to our persistent queries on the what, why and how of inspections.

We started off with a plan. Read what the law says, understood what it means, and then asked everyone who would respond to us about what actually happens on the ground.

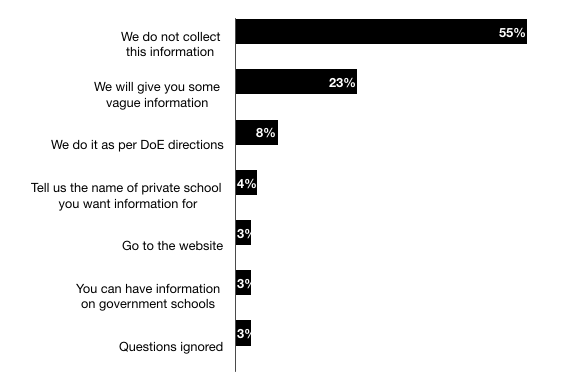

We filed six separate RTIs, three in Delhi and three in Haryana, with each application asking 4-5 questions. We received 116 responses from 20 of the 29 zones in Delhi but they barely gave us any insights into how inspections were conducted (Figure 1).

Finding and reading the law was relatively easy, but not particularly useful in helping us determine what the ground realities of inspections are. For instance, the Delhi School Education Act, 1973 and the Haryana School Education Act, 1995 both said that all recognised schools must be inspected once every financial year.

Through interviews with Government officials and school owners, we found Delhi only inspects 60 private schools each year while in Haryana, officials had not even heard about the clause mandating annual inspections, forget implementation. With all this “legal” knowledge in mind, we designed questionnaires in order to clarify aspects of the inspection proforma that we believed were difficult to enforce or check objectively.

We found, much to our surprise at the time, that government officials and school owners were quite suspicious of 20-year olds asking questions about their jobs. It would not come as a surprise if schools were so hard to get a hold of because they failed to meet one or another regulatory requirement and would rather not speak about it.

Even a thorough reading of the Delhi School Education Act and Rules 1973—a law made four and a half decades ago—would not give a school manager a clear idea about what the government expects. They would have to read 2,000 pages of executive orders, and of course, the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education, 2009. It would be rare to find a school that complied with all of the orders.

Over the course of six weeks, we contacted over 30 private schools in Delhi and only six wrote back. Even showing up at a school’s doorstep, begging for 5 minutes of the principal’s time worked only a couple of times. One of those attempts simply resulted in us being rejected by the principal rather than the receptionist or the guard sitting at the entrance gate.

We entered the corridors of government offices and school compounds expecting accountability, answerability, and transparency. We left disenchanted. These six weeks washed us off our romantic ideas of an ideal government and taught us how things actually work, leaving us wondering where the problem truly lies.

—

Researching Reality is an annual six-week internship program that offers intensive training in policy-relevant research to undergraduate and graduate students of various disciplines.

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.