Street vendors are an integral part of life in India. Vegetables, fruits, milk, clothing—everything people need for day-to-day living is available from sellers who trade in the open-air.

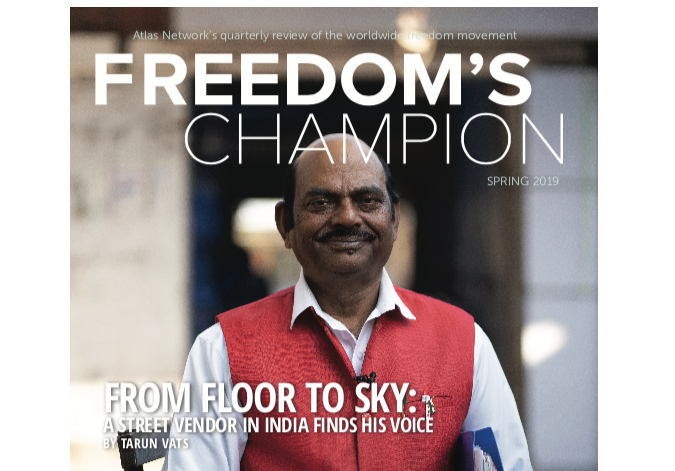

Dinesh Kumar Dixit is one of those street vendors— known locally as a “rehri-parti walla”—and he’s spent the last 40 years standing on a Delhi street, selling the sort of glass bangles that are a speciality of Firozabad, his hometown in Uttar Pradesh. According to India’s Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, there are 10 million street vendors like Dinesh in India—450,000 just in Delhi.

When Dinesh moved to Delhi, his knowledge of bangles was the only way he knew how to make a living. Money was scarce, so he slept on footpaths and loaned out his wife’s jewellery for 28,000 rupees (USD 400) so that he’d have enough money to start a small street vending business as a bangle seller.

But for decades Dinesh was at the mercy of the police, local authorities, and the municipality of Delhi, who would either evict vendors or harass them by forcing them to pay bribes.

“I have maintained a record of every single fine/ challan (ticket) that I have paid for the last 41 years,” recalls Dinesh. “The police would come take my stuff and fine me. I’d refuse to pay bribes and they’d confiscate my stuff. I felt helpless and had no voice to fight the system but I continued my struggle.”

Dinesh and other millions of street vendors in India—who answer to regional names such as hawker, pheriwala, rehri-patri walla, footpath dukandars, sidewalk traders—were all at the mercy of the police before the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act was passed. Centre for Civil Society, an Atlas Network partner in India, was instrumental in advancing this groundbreaking legislation, which helps street vendors like Dinesh have a voice in the system.

The Street Vendors Act secures the rights of street vendors to have a livelihood and fosters a congenial environment for urban vendors to ply their trade without harassment or eviction from the local authorities. The legislation also provides for the establishment of Town Vending Committees (TVCs) that look into matters affecting street vendors. Representatives are elected to the committee to address issues such as new locations for vending zones and identifying vendors.

Today, Dinesh is an elected member of one such Town Vending Committee in New Delhi. He attributes his success to his source of inspiration—his wife—who passed away three years ago.

From living on a footpath to being able to build his own house, Dinesh considers himself a very fortunate man. His family has been his most important source of support and comfort. Today, he shares his home with his son, daughter-in-law, nephews, and three grandkids. Every morning the entire family comes together to pray and enjoy a hearty meal together before Dinesh heads out for work.

Despite becoming a respected member of the community, he hasn’t forgotten his roots. He still opens his shop daily in the same market of Sarojini Nagar in Delhi, where he’s sold bangles for the last 41 years. He goes to the warehouse to pick merchandise, and he and his son run their successful business together. As a TVC member, Dinesh devotes his time to improving the lives of other street vendors. The same local authorities who wouldn’t listen to him now sit across the table as Dinesh challenges them if they fail to listen to the issues of street vendors. “I feel empowered and now with the support of other vendors, I too have a voice in the system,” he says with pride.

Dinesh often spends time with his old friends in the market—other vendors who have celebrated with him as he’s built his business and raised a family. They often refer to his success as “Farsh se Arsh tak”—from sitting on the floor and selling bangles, to now having a seat at the table with local authorities. He represents the changing face of India’s street vendors, who have been empowered through the local support of think tanks.

At 63, Dinesh is planning to run for office as a member of the legislative assembly (MLA) in India. “If the chaiwala [tea seller] can be the Prime Minister of India, why can’t a chudiwala [bangle seller] be an MLA?” asks Dinesh proudly. Indeed, why not?

This article was originally published in Atlas Network’s quarterly publication Freedom’s Champion, Spring 2019 edition. You can view the entire report here.

Read more: https://spontaneousorder.in/street-entrepreneurs-victims-of-executional-paralysis/

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.