Lord Baelish aka Littlefinger said this famous line in Season 3 of Game of Thrones (GoT), a popular fantasy TV series. GoT fans are well aware of the cunning and shrewd intelligence of Littlefinger, but if we were to dissect this statement further and analyse it, we would realise that it also provides some insight into economic theory. Let’s forget Littlefinger-the-character, and focus on this line.

High demand for various needs faced with an inadequate supply of solutions creates chaos in the economy. However, this chaos is short-lived, because it then creates an opportunity (or, ladder) for entrepreneurs to climb and fill this lacuna in the market. Chaos is, of course, a pit for those who lack initiative, those who doesn’t want to take any risk, but chaos is a ladder of benefit to those who are ambitious, determined and opportunistic.

Chaos quite often creates spontaneous order in a society, given the right incentives and a strong rule of law. For individuals who like solving puzzles, this spontaneous order is superior to any order a human mind can design, since for designed order, the specific information required is simply too huge.

Entrepreneurs, by definition, thrive on chaos and try to bring some order. They explore the demands of different products, and fill the gaps by introducing products which common people perhaps have never imagined. The introduction of computers, mobile phones, emails, food delivery applications, taxi aggregator applications… the list is endless…all relied on the opportunistic behaviour of an entrepreneur climbing the ladder out of chaos (like Petyr Baelish). These products are not the result of planned order or the settled economy, but chaos.

These original ideas emerge in unanticipated ways and in unexpected places. The emergence of Silicon Valley or Bangalore as IT hub, for example, happened spontaneously. The unique ideas came from the entrepreneurs which were allowed to manifest in a relatively simpler and conducive environment, provided by the authorities, for these idea to manifest

In recent years, India has seen a start-up boom. The sheer number of start- ups, itself, speaks volumes — it is projected that by 2020 there will be 11,500 tech firms (as compared to 3,100 startups counted in 2014). This is big news for the emerging Indian economy and this will change the way the world looks at us. The emergence could be due to any factor, such as availability and interest of spending in India, evolving technology, creation of bottom-up demand, increased purchasing power, or because of schemes like Start Up India.

The impact of start-ups is not just on the economy but also on social and demographic factors — such as the inclusion of 9% of women entrepreneurs. It is also reported that average age of the entrepreneurs is 28 and approximately 60% of job creation has been by SMEs only.

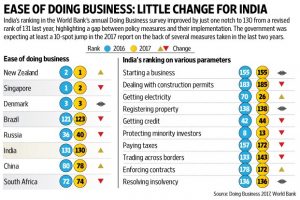

The problem with doing business in India is very simple — too many regulations coupled with high taxes. Despite noble intent, India’s ranking on several market indicators, has been dismal at best, with no change over the past 2 years.

Image Source: http://www.livemint.com/Industry/

Other than this, Indian businesses are also obliged to make annual tax payments that are approximately three times higher than the frequency in China and USA. It doesn’t matter how much Prime Minister Modi says “I see start-ups, technology and innovation as exciting and effective instruments for India’s transformation, and for creating jobs for our youth”. If we really want to help reduce poverty and create more jobs and be the number one in the world, then authorities need to relax a lot of regulations and trust the citizens more.

We need to follow Littlefinger’s suggestion and work towards allowing people the environment to come up with ideas, to try and climb the chaotic ladder, to let them fall and climb up again, and in this process find the best solution to earn profit and help society raise their living standards. Because, “..the ladder is real. The climb is all there is”.

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.