If you haven’t heard of the Kannada film Kantara, there is a good chance you are living under a rock. This film, made with a budget of just Rs 16 crores, became a huge pan-India success. Spoiler alert: You might want to watch the movie before reading this article. This article speaks about two things; the story told in the film and the story made by the film.

Since the beginning of humankind, storytelling has been a significant part of civilization, manifested in captivating art forms like music, dance, and painting. Films reflect the evolution of storytelling and these art forms, while their stories reflect the progression of society. Kantara is a film that narrates the story of a tribal community weaved around their beliefs, rights, and conflicts with the state. While the main plot focuses on how their local deity protects them, the film also poses some interesting questions about the regular conflicts between tribal communities and the State.

For instance, one scene towards the movie’s beginning shows the tribals carrying some vegetation when the forest officer stops them and asks for a permit to take the produce from a reserve forest. An argument ensues when the tribals claim they have a right to collect their forest produce and the forest officer threatens them with arrest. Then the protagonist of the movie says, “We have been living in this forest even before the government was here. Hence the state should ideally take permission from the tribals to operate in the forest”. This might not be a memorable scene, but it raises some interesting questions about the State’s initiatives in protecting the forests.

When the State took upon itself the duty to protect forests through various pre and post-colonial legislations, why did it exclude the humans living in the forests, dependent on them for their livelihood? Don’t the forest communities have a bigger stake in the protection of forests than the government-appointed officials? Why did it take till 2006 for the Indian government to recognize the symbiotic relationship between the tribals and the forests?

The film also depicts similar conflicts related to wildlife hunting and local rituals. These scenes based on everyday real issues of livelihoods and land rights in the forests of India, highlight the rising discord between the police and tribals, thus thickening the movie’s plot. The dispute reaches its crescendo when the government claims that the tribals had encroached on the forest area. Let us pause the movie for a while and get to reality. Telangana’s Mahabubabad district witnessed constant tussles in recent years over Podu lands. While the tribals claim they hold a historical right to cultivate these lands, the government prevents such activities alleging the lands belong to the government.

Let us resume the movie. In the pre-climax scene, the police officials and tribals who were at loggerheads till then realize they are all on the same side, protecting the forest lands from any damage or illegal encroachment. When the antagonist of the movie attempts to take away the property of the tribals, the police help them understand how they can claim legal rights over their land even if it is declared government property.

The narrative on the right to property in India is often associated with the rich and powerful. But in any democracy, this right is quintessential to every citizen, rich or poor. It is a natural right of a human being, and is also part of Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As Nani Palkhivala, a jurist, says, the right to property is the handmaid to other fundamental rights. If the tribals are not guaranteed right over their lands, their right to life and freedom of profession hang in the balance. The film makes a clever point associating the relationship of the tribal community with the state to the police safeguarding their right to property.

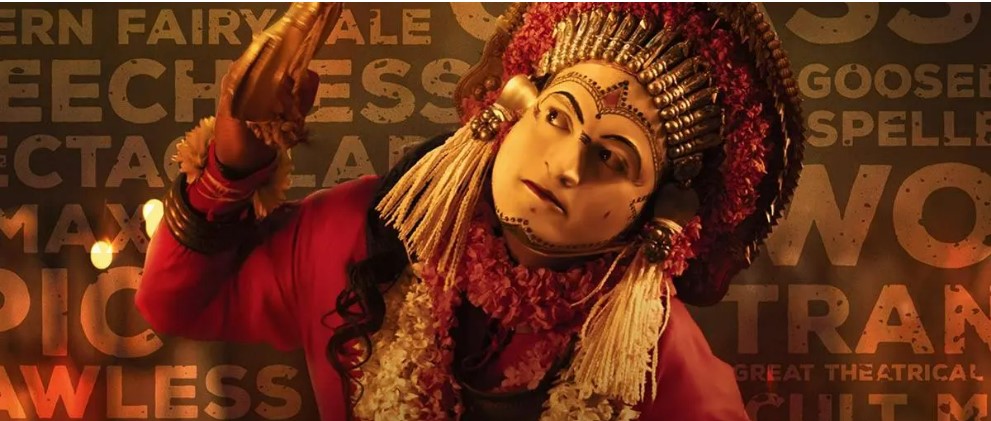

The movie ends with a mesmerising song set to the Bhuta Kola dance ritual in the tribal village. It depicts the protagonist in the form of the local deity entrusting the responsibility of protecting the tribals and the forest. He then mysteriously disappears into the woods. This brilliant scene marks the heights of the art of storytelling. The film initially depicts the State as a disruptive force with low trust in society. Then it captures the transition of this State machinery, gaining the people’s trust by protecting their rights. This is how the State and society evolve in a healthy democracy. When the State formulates and implements legislation considering the sensibilities of the stakeholders, trust builds up in society. When solid institutions are built, individual rights are protected, and the rule of law exists, divine intervention is no longer needed to protect the people. The climax of the film drives home this point beautifully through the drama.

This movie is produced by the fourth biggest film industry in India. With all due respect to the lead characters, it does not have star actors or big budgets. But its spectacular success across the country narrates another story, the story of New India. A new idea triumphing over a seemingly ossified old idea signals free markets. We are an extensive, diverse and aspirational country. We are a huge market of producers and consumers of ideas with merit. When the best ideas succeed in the country, we all have equal opportunities to thrive and prosper in this world. On the one hand, the movie told a beautiful story about the transformation of the relationship between the State and society. On the other hand, the movie made a story with its success, indicating a revolutionary change in the Indian markets.

Read more: Understanding the Knowledge problem

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.