The strong recovery in US domestic demand has spilled over to the rest of the global economy. The largest economy in the world is sucking in goods from the rest of the world at a record rate, either to restock inventories or for final consumption. The US trade deficit in goods was over $93 billion in June; its overall trade deficit was lower because the US has a surplus in services trade. India has been one of the beneficiaries of rising demand from countries such as the US. Indian goods exports have had a splendid run in recent months, at a time when domestic demand is still relatively weak.

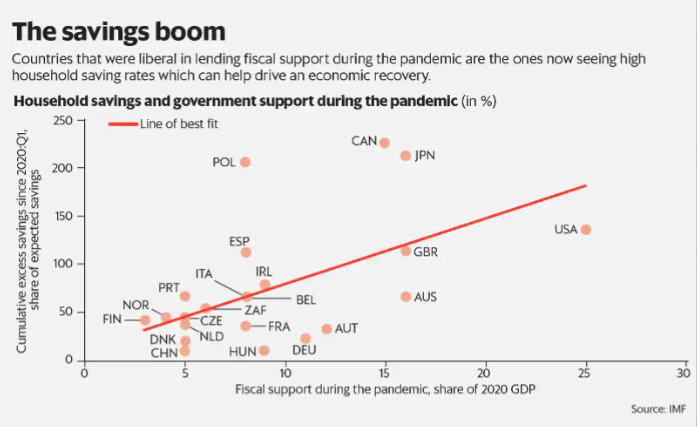

In the recent update to the World Economic Outlook published at the end of July, economists at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have presented an interesting set of data on excess savings in select economies around the world in 2020, including the US (see chart). The numbers can give us some clue about which countries have built up a stock of excess savings over the pandemic months, and can thus support private- sector demand in the coming quarters. What is especially important is that the countries that have high excess savings also tend to be those where governments have pursued expansionary fiscal policies after the pandemic struck.

“Savings tended to accumulate more in countries with larger above the line fiscal support to households, which buffered disposable income,” says the IMF. These savings now open the possibility of private-sector demand, taking the baton from fiscal authorities to keep the economic engine running.

There are two notes of caution here. First, the IMF analysis only focuses on what it describes as above-the-line fiscal support, or direct spending. It does not cover below-the-line support, such as credit guarantees, special liquidity schemes, regulatory forbearance or payroll support. Second, it is quite likely that some part of the excess savings will not be spent in countries where households with excess debt may want to first put their own finances in order.

The main insight is still useful when thinking about the global economic recovery. Countries that provided direct support to the private sector are now well placed to let the engine of private sector demand do more of the pulling. These include economies such as the US, Britain, Japan and Canada. Countries such as China, France and Germany have relatively lower excess savings, thanks to their more modest above-the-line fiscal support. Sweden is a rare country that has actually seen its stock of savings go below normal.

What about India? The IMF analysis cited here does not cover the country. However, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has provided estimates of one part of the total savings in the Indian economy—household financial savings. These had shot up to 21% of gross domestic product (GDP) during the first quarter of fiscal year 2020-21, when consumption had fallen off a cliff during the national lockdown. Quarterly household financial savings have since normalized, and were at 8.2% of GDP in the third quarter of fiscal year 2020-21. High-frequency estimates of total savings—by households, companies and the government—are not yet available.

The data from the Indian central bank deals with flows. The IMF analysis is about stocks. That is an important difference. It is unclear whether there is a modest stock of excess household financial savings to spend down, even as the quarterly flow has normalized. In a recent research note, Axis Bank economist Saugata Bhattacharya writes, though in a different context, that the possibility of excess accumulated savings does not fit very well with the narrative of widespread income losses outside of large enterprises and salaried employees. He also points to the lack of supporting evidence in bank deposits data.

If the correlation between excess savings on one hand and above-the-line fiscal spending on the other holds in India’s case, then it is unlikely that household spending can suddenly accelerate powered by accumulated savings. This is especially so since, as this column noted in October 2020, the Indian fiscal response to the pandemic was focused more on below-the-line items such as liquidity support, rather than above-the-line items such as income support. The former tends to protect the supply side of the economy while the latter tends to support the demand side.

All this is important while thinking of India’s macroeconomic policy conundrum. There is now widespread agreement that the monetary-policy option has run its course, even while there is disagreement about whether this is an opportune moment for RBI to actually begin withdrawing its extraordinary monetary support to the economy. The government continues to run a cautious fiscal policy, betting on the expectation that higher capital expenditure on infrastructure projects will crowd in private-sector investments in the quarters ahead.

The economic impact of the pandemic has expectedly moved from its first stage as a supply shock to its second stage as weakness in domestic aggregate demand. Foreign demand will hopefully provide a buffer till domestic private-sector demand strengthens.

This article was originally published in Livemint on 10 August 2021

Read more: Insuring India

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.