“We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Letter From a Birmingham Jail, 1963)

The consequences of any crisis are not limited to geographical territories but extend outside the national periphery.

The Ministry of Home Affairs’ 2021-2022 Annual Report states that about three lakh Sri Lankan refugees entered India between July 1983 and August 2012 and were provided relief, including shelter, subsidized ration, educational assistance, medical care, and cash allowances.

While Sri Lanka’s streets chanted “Gota Go Home,” its echoes were heard in India. The 2022 Sri Lankan political crisis, due to years of mismanagement, corruption, short-sighted policymaking, and agricultural policies, caused severe inflation, daily blackouts, and shortages of necessities for all. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa resigned in July, preparing for better governance or stepping back in a critical time. The crisis had reached a crescendo with high inflation rates when it became difficult to even purchase staple food and fuel for common people, compelling them to rampage on the streets in anguish. The crises undermined the country’s ability to maintain a stable economy, with the inflation rate soaring to 90 percent.

This article sheds light on the peripheral existence of a community often ignored in the silhouette of economic, political, or social outbreaks.

India officially hosted more than two lakh refugees and asylum seekers. Such a scenario challenges the Indian government regarding the management of their livelihoods, social integration, and economic turmoil, among others.

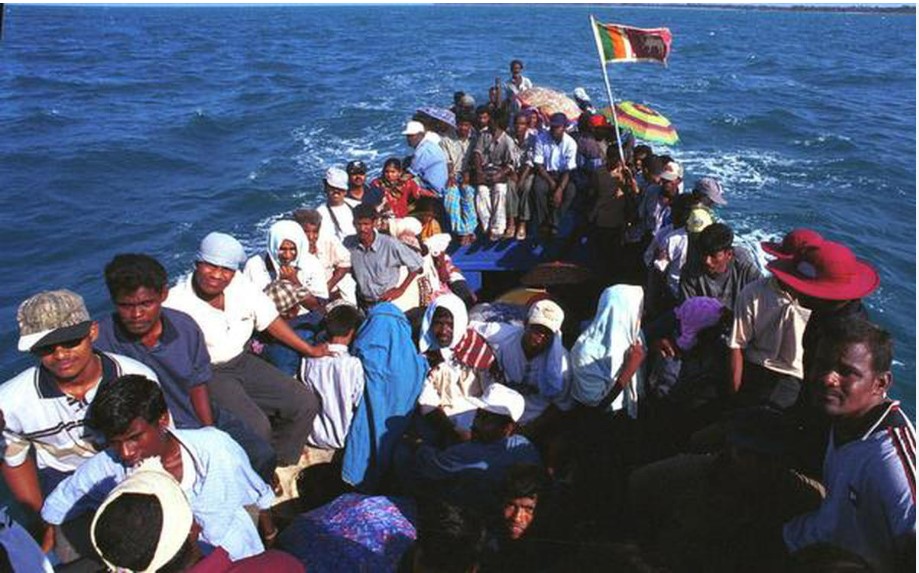

Tamil Nadu has witnessed the impact of Sri Lanka’s unprecedented crisis in the form of asylum seekers. The legality of this cross-border movement takes a back seat when communities are desperate and ready to risk it all. Sri Lankan asylum seekers in the recent crises entered in batches, usually by boats, to Serankottai beach in Dhanushkodi to escape the exorbitantly high prices. The Tamil Nadu government ensured food grains, vegetables, and medicines as humanitarian aid alongside setting up rehabilitation camps in the Dindigul district. The government also decided to construct 7,469 houses in refugee camps at Rs 231.54 crore to ensure a safe and dignified life for the crisis-hit community.

Since the 1960s, Sri Lankan refugees have taken shelter in Indian territory. The Black July riots and Sri Lankan civilian war have caused the influx of thousands of asylum seekers. According to India’s Home Ministry, 58,843 Sri Lankan Tamils were residing across 108 refugee camps in Tamil Nadu as of 2021. Besides, around 34,000 refugees were staying outside the camps, registered with the state authorities.

This flow of people from places of denial to the regions of guarantee poses vast economic, social, political, and environmental impacts on the host country. Right from arrival, refugees compete with local citizens for limited resources such as water, food, housing, and health-care services.

It is arduous to quantify the contribution toward social expenses and calculate the government’s available funds for refugees. Most forms of refugee impact are felt at the local level. Since refugees are desperate to earn a living, they are willing to work for lower pay hampering the informal sector’s overall payroll. Their entrance into the labor market generates a rivalry between them and local laborers. Contrarily, refugees are also susceptible to manipulation due to ignorance and constant fear in a distant country.

The prospect of a swelling population of desperate people clinging to economic recovery in their homeland has its own risks. In their constant hope for improvement in the homeland, refugees do not feel a sense of belongingness towards the host nor an urge to invest in improving their livelihoods. In September, the Sri Lankan government appointed a committee to facilitate the repatriation of Sri Lankan refugees from India. However, only 3,800 out of 58,000 wanted to return to the unpredictability. After witnessing acute shortages and long-term deprivation, debt sustainability and closing financing gaps are now elusive dreams.

From the very beginning, India has espoused an ad hoc approach to various refugee influxes. It is neither a party to the 1951 Convention on Refugees nor the 1967 Protocol. India does not have a codified law on the status of refugees posing issues, confusion, and massive exploitation. This government approach has resulted in the inconsistent treatment of different refugee groups. Some groups are granted a gamut of benefits, including legal residence and ability to be employed, whilst others are criminalized and denied access to basic social resources. For instance, while one government school may admit a child deemed a refugee by UNHCR, another may be within its rights to deny admission because he/she is an “illegal” resident.

The legal status of refugees in India is governed mainly by the Foreigners Act 1946 and Citizenship Act 1955. These Acts do not differentiate refugees fleeing persecution from other foreigners and apply to all non-citizens equally. Under the Acts, not having valid travel or residence documents is a criminal offense. These provisions render refugees liable to deportation and detention. India lacks a well-defined concept and concrete legislation on the subject of “Refugee” and has adopted international notions and definitions about the refugee issue. However, continuous changes in the international political state of affairs also affect India’s refugee discourse. Humanitarian migrants are often excluded from formal systems for socioeconomic inclusion and possibly socially marginalized because of denied access to government-issued documentation, affecting themselves and future generations.

While headlines are crowded with figurative analyses, each migrant refugee struggles to fill cultural gaps, find livelihoods, and be accepted and recognized. Refugees and asylum seekers exist in gray areas, ushered in failure to socially integrate into society while facing a constant “Us versus them” narrative. This predicament is linked to years of government neglect and a fundamental policy vacuum. Refugees need not be an unmitigated burden on the host countries, especially if they are provided opportunities to utilize their productive capacities, and if the international community wholeheartedly endorses them with the principles of international solidarity, cooperation, and responsibility-sharing.

Read more: Tackling Shortages in Affordable Indian Urban Housing through Free Market Forces

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.