India’s 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the biggest democratic activity in terms of scale, also unsurprisingly has the distinction of being one of the most, second most to be more precise, expensive affair of its kind in the world. Indian ministerial candidates collectively spent an estimated 5 Billion $ or almost Rs 35,000 crores in their election campaigns, making 2014 the most expensive election in the nation’s history. While this figure may seem outrageous at first, it makes sense that parties spend so much considering that we have a voters’ base of about 900 million. How do you ‘con’vince 900 million people to vote for your political party?

With expanding media platforms, the avenues for political parties to influence the masses moves beyond the traditional rallies. Digitisation of India is best seen in India’s election spending. Social media ad spending alone may amount to Rs 12,000 crores in 2019. In the competitive political market of India, political parties have to spend money, not just to be visible but also to push their ideas and thoughts on any given issue. Where is this money coming from?

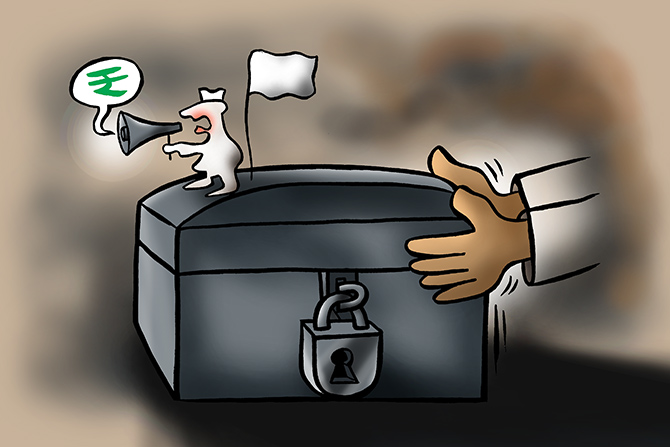

That is difficult to say. Political funding in India largely remains ‘under the table’ despite the many ‘reforms’ introduced by the government. But what is it that’s making our political funding so opaque? Have the government policies really been an effort to make the process more transparent or are we moving towards making the political parties immune to all kinds of scrutiny?

Let’s look at some of the institutional loopholes that allow electoral funding to remain non-transparent and go unaccounted for:

- Amendment through the Finance Bill of 2018: Being the last full budget before the general elections, the Finance Bill 2018 saw obvious backlash and pandemonium. But the one amendment that was passed without any debate was the one proposed to the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010. This amendment retrospectively exempt political parties from scrutiny for receiving foreign funds, which had been a matter of legal contention for major political parties.

- Cash Payments: Political parties are permitted to receive anonymous cash payments not above Rs 2000. While this limit is lower than the earlier Rs 20,000, it is not effective in that it doesn’t put restrictions on the number of times these donations can be made by a single person. The only difference this has over the earlier limit is that now you’ll need to show big donations as smaller amounts. Hence, it is a mere sham in the name of reducing black money in political funding as long as no cap is set on the anonymous donations that a single party can receive.

- Electoral bonds- Introduced in January 2018, the electoral bonds were seen as a massive step towards controlling black money within election funding. But over time it has started to be seen as an instrument used by the government to make election funding even more opaque. These bonds are available in multiples of Rs 1,000, Rs 10,000, Rs 1 lakh, Rs 10 lakh and Rs 1 crore. Unusually for an instrument of such high-value, electoral bonds can be anonymous. Independent entities can donate large sums to a party without having their identities disclosed to the Indian voter. OP Rawat, former Chief Election Officer of India, said that Electoral Bonds are a ‘Threat to Democracy’.

With better understanding of where the major flaws lie, let’s now look at what can be done to bring transparency and accountability in the political system:

- Bringing political parties under the ambit of the Right to Information (RTI) Act:

In 2013, a directive of the Central Information Commission brought 6 national political parties under the ambit of RTI. In 2018 however, the Election Commission issued an order contradicting the CIC and stating that political parties do not come under the ambit of RTI. All this amidst the outright refusal of political parties to disclose their funding sources. The matter has also been escalated by many activists to the Supreme Court citing the CIC’s directive. Many argue that EC has no jurisdiction in the matter and the decision of the CIC is uncontestable. The lack of political will across the board has introduced a lot of corruption in the process and this still remains a far fetched reality in India.

2. Limit anonymous donations:

Making anonymous donations to political parties is very convenient. In many cases, this anonymity exists only for the voters and the parties accept anonymous donations from entities who influence policies in their favour in return for donations. The bigger the sum of your donation the more influence you’d be able to get greater political favours. This is an obvious and immediate step which should be taken given that political parties have gone to the extent of declaring 100% of their donations as anonymous.

While these are methods to make monetary donations to political parties more transparent, what can be done about abstract donations extended to political parties in the form of favours? If someone volunteers to bear the logistical costs of a rally, how will we account for donations made in this indirect manner? Asymmetry of this kind is very difficult to correct, or even discover.

This implies that even after making monetary donations to political parties transparent, the problem may still persist. Having said that, introducing monetary transparency would be a step towards correcting the lack of accountability of political parties. If anonymous donations are not controlled, the concept of one vote one person one value is meaningless. Informed choices do not come from uninformed masses.

Read more: https://spontaneousorder.in/crime-and-politics-the-goondas-holy-grail/

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.