During the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, Madras, now Chennai, was the playground of conservative and liberal scholars, reformers and politicians.

The Madras Liberal League moderates had played an active role in the freedom movement and nation-building. They were all well-reasoned men and women, with sound knowledge of public affairs, believed in pragmatic reforms through constitutional methods, advocated principles of economic freedom, individual liberty, private property rights, free enterprises, rule of law, freedom, and universal peace.

Anabolic steroid pill, safe bodybuilding anabolic – heroes past and present pharma tren a100 proform cr 610 (# pctl55810) home weight system manuals, user guides, and other materials.Alas, after India’s independence in 1947, this diversity of thought gave way to one-sided discourse dominated by a few with muddled ideas of Fabian socialism and even murkier, Communism.

The few leaders who favoured putting into place institutional mechanisms and backed the rule of law, were pushed into the background. Even earlier, during 1930-1947, leaders and scholars whose views were genuinely liberal, found themselves marginalized in the mainstream debate and discourses of public policy.

Thus, the first 40 years of independence was democracy in motion, minus economic freedom. It was cynical to argue about individual liberty, private property rights, free enterprise and rule of law, all of which were part and parcel of the original Constitution adopted in 1950.

Towards the end of the 1960s, Tamil Nadu witnessed a major shift in politics away from the Congress regime. This was celebrated as a victory of the Dravidian movements, which allegedly championed social justice and empowerment of backward communities.

Interestingly, none of the Dravidian leaders were part of the freedom movement or believers in constitutional principles. Instead, they were all born out of hate speeches delivered against some or the other community, political parties and were basically, crude practioners of language politics, which pitched them against national integration and regional unity. Over the years, these anomalies were incorporated as film scripts by Dravidian parties, all in the name of social justice.

Amid these dangerous developments, which began in the late 1960s and early 1970s, there were hardly a well-reasoned thinker, scholar and political leader in Tamil Nadu, who could highlight the principles of liberalism embedded in the Indian Constitution.

Under such trying circumstances emerged a man of an entirely different persuasion, pitched against the dogmatic policies of the Communists, Socialists and the state control raj of the Congress and Dravidian parties in Tamil Nadu.

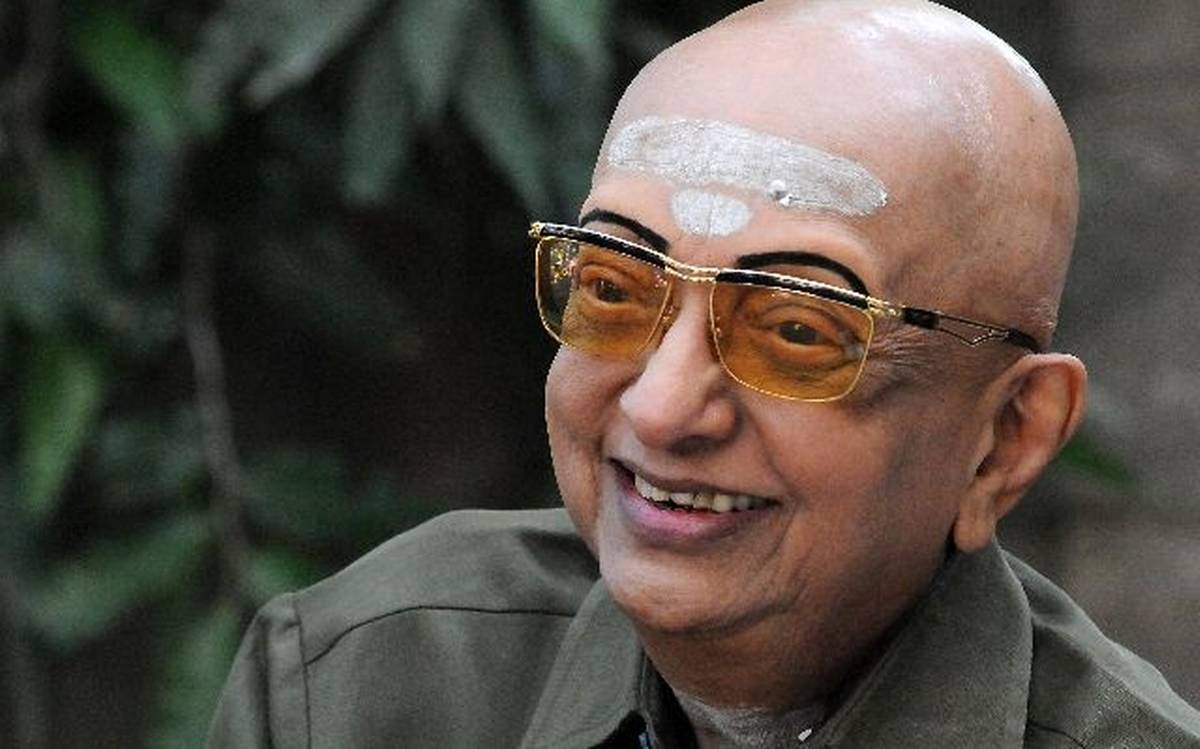

Cho Ramaswamy was a multi-faceted personality, a scholar, thinker and above all, a man opposed to the tyranny of Dravidian politics. He was among the few political analysts who had a fine balance of reason and logic. He used them to impact public policy with the help of humour, sarcasm and biting satire.

When India was at the peak of her socialist dictatorship under Indira Gandhi, Cho was drawn to the ideas of another liberal titan, C Rajagopalachari. Cho admired and met Rajaji in the 1970s. He also campaigned for the Swatantra Party and the Janata Party.

Srinivasa Iyer Ramaswamy or Cho was born on October 5, 1934, in then Madras in a well-respected lawyer’s family. He was popularly called Cho by his family, inspired by the ancient South Indian king, Raja Raja Chola.

Cho completed his education in Chennai; school at Mylapore, intermediate from Loyola College, a B.Sc. Geography degree from Vivekananda College and a law degree from Madras Law College.

From 1957 to 1963, he practiced as a lawyer in the Madras High Court and was legal adviser to the T.T.K. & Co. group of companies in Chennai till 1978.

Cho wore many hats. He was a lawyer, an investigative journalist, writer, political analyst and commentator, editor of a popular Tamil weekly magazine, a powerful orator, author and parliamentarian. He combined these talents with being a cine actor, playwright, movie director and a socio-economic cum political analyst, who was appreciated by all, including his foes.

Cho Ramaswamy was nominated as MP to the Rajya Sabha from November 16, 1999, to November 16, 2005, and made his presence felt there. In his quest for exploration, he also did a stint as president of the Peoples’ Union for Civil Liberties in 1981-82.

According to senior journalist and publisher N Ram, Cho “was a lifelong conservative and never moved from being on the right of the political spectrum. He maintained his political conservatism all his life, choosing to judge governments at the Centre and in Tamil Nadu by their policy and performance on issues that mattered”.

Cho’s classic 1968 satirical play, Muhammad bin Tughlaq was a roaring success. He later turned it into a movie, which revealed the anatomy of a government in a democracy. His political magazine, Thuglak, launched in 1970, named after his celebrated play, became a classic of modern literature for political satire, writings, editorials, essays and cartoons. His editorials on issues of national interest were all scholarly, martialed on evidence and facts. Over the years, political satire took different forms in Thuglak. His interactions with readers was a celebrated event in Tamil Nadu over the next five decades. Happily, it continues to cast a spell five decades after its inception.

Cho was an unflinching critic of the Soviet Union and its model of central planning and socialism. He wrote scathing articles during the Indira Gandhi period on the murky world of socialism, pseudo-secularism and Communism.

Cho once famously said: “I am against Communism because it is against the nature of man. A talented man cannot be asked to be satisfied with what a man totally devoid of talent is able to obtain from life. Communism makes machines of men.”

He was a fearless journalist. Cho fought against the authoritarian dictatorship during the Emergency over the principles of freedom of expression in general and of freedom of the press. His famous quip, “After Independence, we lost sight of our duties and remembered only our rights,” is still recalled.

Cho was one of the earliest backers of economic liberalization of 1991, with deep knowledge on how it would benefit the poorest of the poor. He also supported 100% foreign direct investment (FDI) in retail trade, even while many of his close friends disagreed. His logic was simple: “When capitalism thrives, the poor get to be employed usefully and profitably.”

Cho was not the one to shy away from challenging anything that went against national interest and the economy. He was a staunch critic of the LTTE, foresaw the danger and the security threat it posed, both in India and Sri Lanka, and issued warnings accordingly. But no one took him seriously, even after the Tamil extremists had assassinated Rajiv Gandhi!

AR Venkatachalapathy wrote a nasty obituary on Cho’s death in December 2016. It came as no surprise because the writer, a known Dravidian propagandist and historian, had been at the receiving end of Cho’s biting satire. Another Cho baiter, R Vijaya Sankar, trashed him in the Frontline magazine, revealing that the late maestro’s enemies had finally breathed a sigh of relief at the passing away of their bete noire.

Apart from the political economy, Cho wrote copiously with great authority on religion and culture. According to N Ram, “Cho, a conservative, who was endlessly curious about other people’s ideas and beliefs, respected ideological and political differences, spoke the truth as he saw it, was steadfast in his defence of free speech and democratic discourse, and when things threatened to get out of hand, was able to lighten the atmosphere with his wit, spontaneity, and comic genius”. Truly, a man of many parts.

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.