For all it’s good and bad, this lockdown has hopefully taught a lot of valuable lessons, some of which are simple, particularly the one about central planning. Let’s take this one for example; during the initial phase of lockdown, while the government had closed almost everything, they had still allowed inter-state transportation for essential goods. It was only after a few weeks that government officials realised that despite being allowed, the truck drivers were not running.

After having paused inter-State transport for weeks, officials finally figured out why the truckers weren’t running. The reason turned out to be intuitive and straightforward to everyone in the supply chain. If local dhabas and rest houses were closed, how were drivers supposed to drive throughout the night and reach different parts of the country?

Not to mention the lockdown provided a great opportunity to local police to force truck drivers who are stuck to pay bribes. Something so simple, and yet so essential to the supply chain, had skipped the notice of the officials who had made the policy. It was because the officials do not drive trucks. They did not speak to anyone who does before making the policy. They just assumed they knew and understood everything.

Thus, when recently, a new list of businesses that were allowed, dhabas and vehicle repair shops along the highways, both essential to the supply chain industry, were added. Now, the government had learnt better after having paralysed the supply chain for weeks.

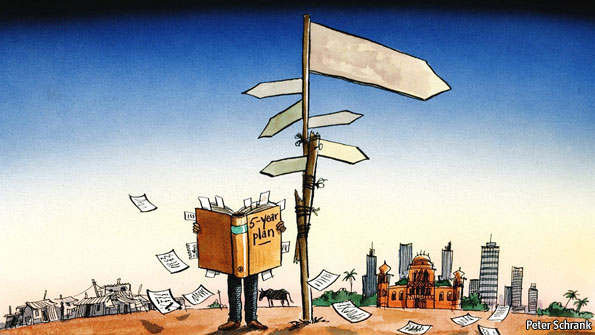

The important lesson here, which I hope babus sitting in Delhi would learn (but am not going to hold my breath), is one of humility. Those sitting on the top cannot even begin to understand what is or is not essential for those working at the bottom. The economy is an intricate system of people working together, depended on each other, not a series of numbers on an excel sheet policymakers can read and figure out. People are not pieces on a chessboard to be moved around at will and fancy of someone with no real stake in it.

And this is why comprehensive central planning schemes never seem to work, despite their best intentions and efforts. Central planners tend to forget that ground realities are always in flux, always responding to the need of time and place. Even if bureaucrat in Delhi manages to get the required information to make a policy about, say a village in Kerala or Assam, by the time the information is sent to Delhi, the policy framed, and implementation on the ground, the prevailing conditions would have changed. That is if the first, and most significant problem of central planning, the “Knowledge Problem” as the economist FA Hayek called it.

History has shown us time and again that no government structure can have all the knowledge all the time required to make a decision. No amount of technical expertise, degrees, and collection of subject matter experts can replace the unique nature and importance of local knowledge which is always in a flux. Therefore, it is better when people closest to the ground come up with a solution by themselves. If the state must interfere in the economic affairs of the people, at least the government closest to the people, the local administration should be the one to frame and implement policies.

Read More: Local Government and Grassroots Democracy in India

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.