The Truman Show, a 1998 classic starring Jim Carrey as Truman Burbank, follows the life of Truman Burbank, an ordinary man living in Seahaven, who slowly discovers that his entire existence is an elaborately constructed television show broadcast to millions. Every aspect of Truman’s life, from his intimate relationships to his job and even the physical surroundings, such as his town, is a set and system in place to monitor and track his movements. He, without realising it, is under constant surveillance. The film shows how events in his life are staged, and his actions are manipulated without him realising it.

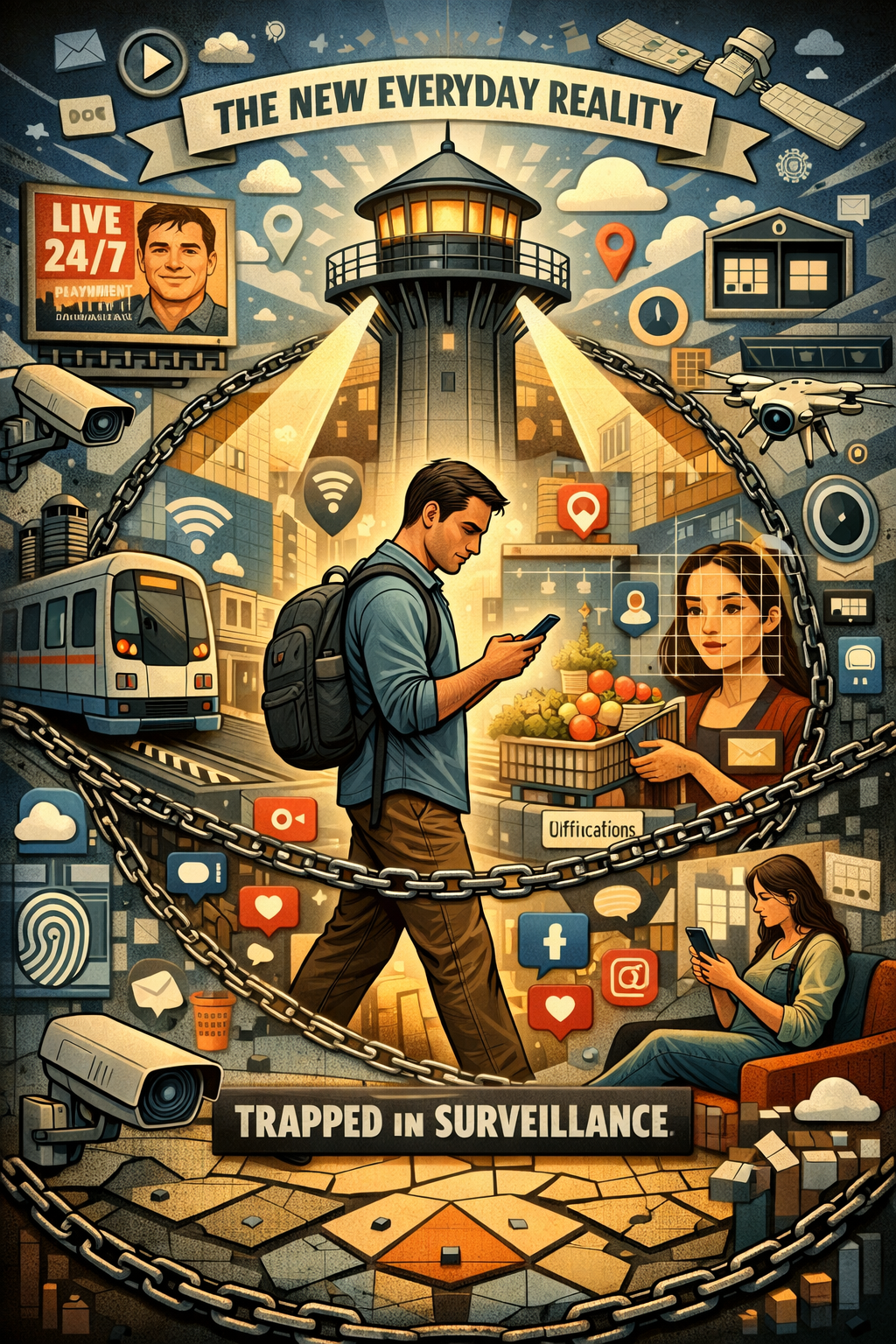

While The Truman Show is a satirical film, we may not have realised how closely Truman’s life mirrors our everyday reality. Our daily activities, as small as taking the Delhi metro from Green Park station to Dilli Haat INA, buying everyday essentials such as groceries (using UPI o bank transactions), and even the doom-scrolling that we do on Instagram, are all under some form of surveillance, both physically and digitally. Unlike Truman, we have no single Christof who monitors or tracks our movements. We live in a world where multiple institutions and systems are in place that keep a constant eye on our movements. Every time we tap “Allow”, we trade privacy for convenience; we continue the same bargain Truman never consented to, except we do it willingly. This surveillance has become so internalised that, like Truman, we have also started behaving in a certain way, where our actions and behaviours are manipulated because of this surveillance.

Long before smartphones, Michel Foucault warned that the most effective form of power is one that makes people police themselves. He introduced panopticism, a theory that talks about how individuals start self-regulating their behaviour because they sense that they are always being watched. He came up with this idea based on the Panopticon, a prison system designed by Jeremy Bentham that essentially has one watchtower, and the prison cells are arranged around it such that every prisoner can be monitored from the watchtower. However, the prisoners cannot see when someone is watching over them from the tower. This leads to them thinking they are under constant surveillance, and therefore they self-regulate their behaviour.

Now, in our everyday life, the world in itself has become a panopticon. Individuals shape their behaviour in a certain way because they feel they are always visible to someone. This idea of always being in someone’s sight has led to internalising self-regulation.

What makes contemporary surveillance different from the panopticon Foucault described is that it no longer feels like confinement. It presents itself as a choice. The watchtowers now are the apps, platforms, and policies that promise efficiency, safety, and connection. We are not forced to remain visible; we are “encouraged” to be. Visibility is rewarded with convenience, validation, and access, while opting out often comes at a social or economic cost. In this world, surveillance does not operate through overt coercion but through subtle incentives, making self-regulation not an act of fear but a habit of everyday life.

Unlike Truman, whose moment of realisation led to an exit, our surveillance has no clear walls and no single door that will save us, because an overwhelming number of us will always prioritise convenience over privacy. The systems that watch us are normalised and embedded into everyday convenience. There is no dramatic escape, only quiet compliance. In this sense, the tragedy of our reality is not that we are watched, but that we have accepted watching as the cost of convenience.

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.