On January 1, 1950, two days after India became the second country in the world to accord recognition to Communist China, Peking (now Beijing) dropped a bombshell. It announced that the liberation of Tibet was one of the basic goals of the Peoples’ Liberation Army (PLA).

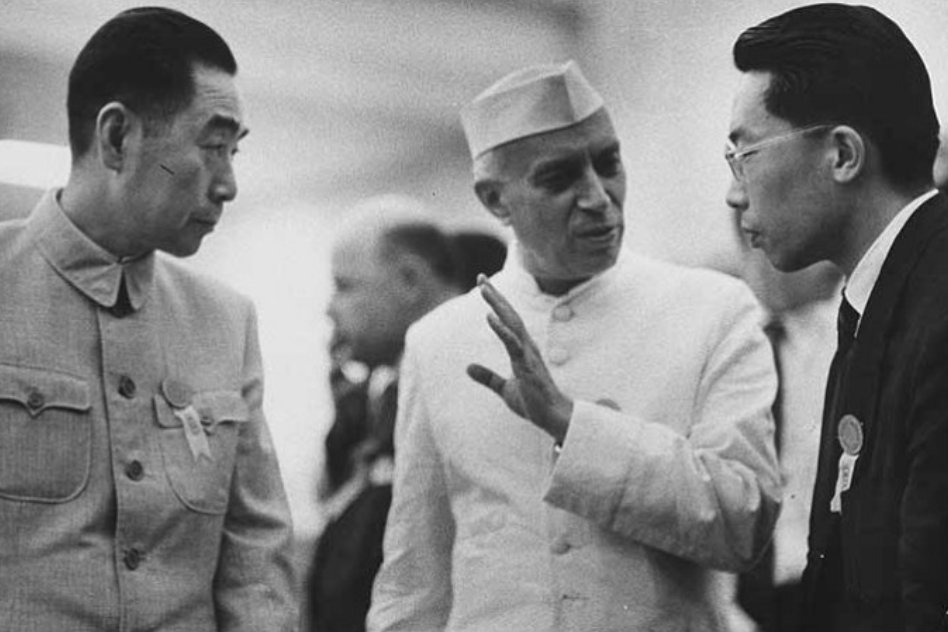

The timing could not have been more fortuitous. The Chinese statement issued from Beijing in detail made no mention of any Indian presence or role in Lhasa. Blinded by dark ideological lenses, the vision fogged by China’s “bhai-bhai” chimera, India and Jawaharlal Nehru refused to see the true nature of China’s intentions in Tibet. It didn’t even grasp that China was hitting out at India when it gave a call in the 17-Point Agreement, signed in May 1951, to “drive out imperialist aggressive forces from Tibet”. Who were these imperialist forces? From the benefit of hindsight, it would be safe to assume that it was India that the Chinese were referring to.

This, when the Economist in 1949 was advocating Indian lead support for Tibetan Independence, followed by recognition by U.S.A and U.K., but admitting that “if India preferred to abandon Tibet to its fate, the Western Powers were in no position to object to a Chinese reconquest of Tibet.”

Under the circumstances, give it to India’s unsung libertarians. No soon after Tibet was overrun by China, Minoo Masani, then still years away from forming the Swatantra Party, brought up in Parliament Mao Zedong’s message to CPI leader B.T. Ranadive of “good wishes for the liberation of India and their hope that India will go the China way.’’ Noted then Dutch Ambassador to India, W.F. Van Eekelen in his seminal account Indian Foreign Policy and Border Dispute With China: In Masani’s view, China had thereby destroyed “any illusion about friendship, any cordiality and about comradeship in Asia” and cut Asia into two parts – Communist and non-Communist Asia. It was a warning from Masani long before the 1962 Sino-Indian war, that the invasion of Tibet was the first sign of the Chinese aggression. It went totally unheeded.

Contrast it with Nehru’s shocking naivete. In his book, ‘Will Tibet Ever Find Her Soul Again?’ French writer Claude Arpi reveals that Nehru’s India supplied rice for the invading PLA troops in Tibet when they were busy rampaging and decimating the Tibetan way of life and culture in the early 1950s.

According to Arpi, to overcome the food crisis in Tibet, Mao looked towards India. S.K. Krishnatry, the Indian Trade Agent in Gyantse, mentioned that the Chinese government had requested India “for an agreement allowing facilities for the transport of food and other supplies through India”. The Chinese government wanted transit facilities for 10,000 tonnes of food grains through India, as a special case. Delhi first agreed after careful consideration to allow the transit of about 3,000 tonnes of rice to Tibet. “While pointing out the transport problems involved in the proposal, the Government of India expressed their (sic) willingness to consider it together with all outstanding issues regarding their position in Tibet,” wrote Krishnatry. Sadly, but not surprisingly, the Tibetan part of the story was soon forgotten.

In his 1955 book, ‘In Two Chinas’, New Delhi’s first and long-standing envoy to Peking, K.M. Pannikar noted: “I knew, like everybody else, that with Communist China cordial and intimate relations were out of the question, but I was fairly optimistic about working out an area of cooperation by eliminating causes of misunderstanding, rivalry etc.”

Despite the Indian Prime Minister’s grandiloquence on recognising China, the Shanghai Observer offered its own interpretation of why India had followed the course it did: “it is a matter of Nehru weighing his desire for US assistance against his need to assume the hypocritical role of a progressive to deceive the Indian people.’’

Later, when Nehru was riding high on Non-Alignment, Chairman Mao was not too impressed. “Mao’s dictum that neutrality was camouflage and that a third road did not exist was conducive to criticism of India in terms of Marxist dialectics,” noted Van Eekelen.

Even after the conquer of Tibet in the mid-1950s, when the country was awash with slogans of Hindi-Chini bhai bhai, celebrating the traditional friendship of two ancient civilisations like never before, Indian libertarians had their eyes wide open to possibilities of every kind – including a potential military invasion by an ambitious Communist power.

Once the formation of the Swatantra Party was announced in Madras on June 6, 1959, by C Rajagopalachari and Minoo Masani, some of India’s brightest and most progressive minds joined the new party with views that embraced free enterprise and stressed on closer ties with the West.

Two early members of the Swatantra Party, Mariadas Ruthnaswamy and NG Ranga, recognised trouble when they saw it; they were not in the mould of other Indian opposition parties, who opposed the Congress, but mouthed Socialist platitudes while doing so.

NG Ranga criticised the repeated professions of friendship, not only to the Chinese people and government but also to Chinese claim of sovereignty over Tibet.

To the Swatantra Party, the Non-Aligned Policy was moribund, and the need of the hour was closer ties with the US and West, which was anathema to the official Indian position.

Ruthnaswamy, at the First National Convention of the Swatantra party in 1959, declared that the policy of Non-Alignment had become odious. Later, at a memorable speech on foreign affairs dated June 23, 1962, which turned out to be prescient, Ruthnaswamy said: “Now, the independence of Tibet is absolutely necessary for the defence of India. We should have protested against the occupation of Tibet by China…. we allowed Tibet to be gobbled up by China.” Barely a few months down the line came the Chinese invasion of India, with disastrous consequences.

In the post-1962 period, when India’s territorial integrity had been violated and her soil occupied by a Communist power, Swatantra Party was convinced that the concept of Non-Alignment was meaningless.

The Chinese border war had justified its argument. The Swatantra Party, at its Second National Convention, called upon the Indian people to maintain vigilance against the possibility of further appeasement and capitulation to the claims of Communist China.

On November 15, 1965, in the aftermath of the Pakistan war, Minoo Masani gave a speech in the Parliament outlining his vision of foreign policy for India. After diagnosing the failure of the government, Masani proposed a typically liberal and workable agenda. The measures suggested included formation of a regional security alliance, support to Tibet and Taiwan, diplomatic relations with Israel and acceptance of help from both the US and USSR.

Nonetheless, Masani, in the highest traditions of liberals, spoke some home truths – like India’s isolation at the UN, despite the successes against Pakistan in the 1965 war. “I am quoting from the Hindustan Times of 23rd October: According to the PTI, the spokesmen of 63 nations were neutral and did not go beyond appealing for peace, 19 were hostile to India and, of these 19, 11 were members of the Arab League. 3 made passing references but did not say anything. 25 ignored the issue. Out of 110, not one spoke up for us. This is something that cannot be side-tracked by recording satisfaction at our success in the Security Council,” he stated, rather clinically. The need of the hour, therefore, in Masani’s views was to give Indian diplomats “a product they could successfully sell in the councils of the world.”

It took roughly four decades for Indian foreign policy to make amends. Who knows, if India were to be as Non-Aligned today when the Chinese PLA is gnawing at its borders, as it was in 1962, the outcome could well have been entirely different.

Read more: SO Musings: Swatantra Liberals and Indian Foreign Policy

Post Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of CCS.